A Strange Splendour 🌆

Revisiting Los Angeles via a 23 year old web zine:

What was I writing about 23 years ago? I was waxing lyrical about the high camp of a vanishing downtown Los Angeles. I published these essays in an online zine M and I edited called Die Cast Garden. I coded it using Dreamweaver made illustrations with Fireworks (before Adobe bought this software the pair were glorious, but I digress.) I found the zine on the miraculous Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. 20 some years ago, Die Cast Garden was my answer to publishing in general—I couldn’t find an agent or publisher for my work so I made zines—xeroxed paper ones and HTML websites.

Last month, The Atlantic broke the news that Meta has used LibGen, an enormous database of copyrighted material, to train its AI, all while big publishing goes after The Internet Archive, a registered library using controlled digital lending and legal fair use.

When I look back at this work and its context, it’s not with nostalgia now but with disorientation. How did we get from there—hand-coding websites that promised freedom from publishing hegemony—to this? Mega corporations indulge in piracy on a vast scale. For what?

I am playing cat and mouse: deleting X, coming off Meta, migrating from Substack Substack (there are problems of another sort there.) As I shuffle, it feels like disappearing.

But here is something the good internet has salvaged; may it be a boon.

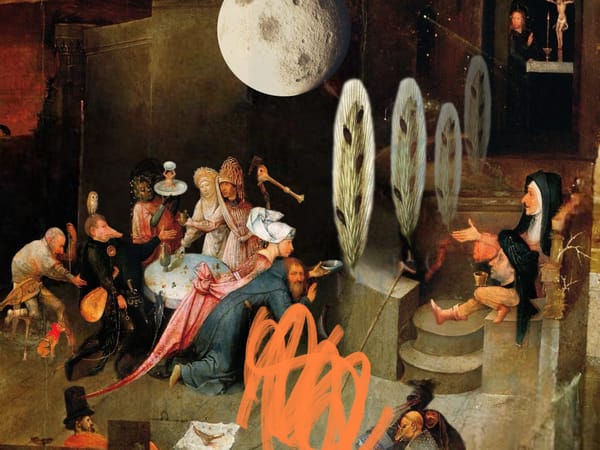

A Strange Splendor

When I moved to Los Angeles, I refused to be at home. I couldn't go blonde or schmooze at parties. I wouldn't drive a car. I walked it. Almost as a dare to myself, a dare to love this sprawl of a city, I began my search for its heart, for an L.A. I could claim, an LA of spooky movie palaces and other people walking, of Cumbia and cafeteria comfort food.

The search ended downtown, in the heart of the jewelry district. I walked down Broadway and came upon the then-closed Bradbury building-- it was empty and dark, still. Gray rays of sun made their way down from the glass ceiling to illuminate the lacy iron work and gorgeous red wood. It was like looking into some strange church, all delicacy and logic, its congregation vanished while outside life throbbed: salsa boomed from storefront speakers, the Giant Penny sign a modest sun, a boot seller cried "Pasale! Pasale!," girls and old women passed hand in hand as homeless men shuffled by and a bride with her bouquet and bridesmaid made their way down Broadway to a store front which offered Marriages and Divorces.

Now, anyone can enter the Bradbury Building; light floods it. It has been refurbished it to its original grandeur. A friendly guard will give you an information sheet explaining the building's history. The only building by architect George Wyman, his dead brother spoke through an Ouija board, and suggested he take on the project.

[The Bradbury Building was made famous as a location in Bladerunner]

We have the treasure of the Bradbury building. So many other places, parts of the city's history, have been torn down or left to decay. Much of the older architecture downtown has been reclaimed as mini-malls or "indoor swapmeets," elegance replaced by an overwhelming abundance. It's a bustling marketplace where you can get anything you want, and a great deal you wouldn't want: fake doggie doo, fresh mangos, five dollar girdles, mood lipsticks, stereo equipment, and wind up GI Joes that crawl and shoot.

In the Broadway Arcade, this array of goods so distracted me at first that I did not look up, past the vendor's plastic canopies to see the beautiful ceiling: hundreds of smog-encrusted glass panes forming an archway overhead, unable to compete with the cavalcade of goods below. Everywhere-- dark forgotten corners, whole floors of abandoned, with all the activity going on below, at street level.

The Los Angeles and Orpheum theaters still show films, but most are now storefronts, the rest of the buildings vacant. One can still see the Palace's shabby Florentine ceilings, or the baroque Bison heads on the Million Dollar Theater, once an Evangelical church and now up for lease. The Cameo houses electronic equipment and gold; The deco Roxie and the Globe theaters are full of bargain clothing. The State is a church, the Rialto now Discount Fashion. The Tower is empty.

A year ago, Broadway was under construction. Under generations of asphalt lie railroad ties. They were revealed during excavation; this place is always becoming something else. Ingenious communities sustain it, transforming it into a place of wonder and juxtapositions. Look up: the Pre-Columbian figures on the mural at fourth and Broadway dwarf you and tower over the "Little Angels" storefront filled with frothy communion gowns. On the same scale, a 7up bulletin board from the 80's offers sun-bleached new wave.

Like everyone else bustling about, I come to shop and eat, go to the Million Dollar Botanica where you can pick up some Good Luck Floor Wax, cowry shells or a statue of scabby Lazarus while your prescriptions are filled, or stock up on dress socks at the Sixth Street Arcade, window shop for wedding gowns and work up an appetite. Then you can go to the neon and sawdust commotion of the farmer's market. "Since 1917," new red banners proclaim. Load up on pupusas and Tamarindo soda and check out the watch case by the sea food.

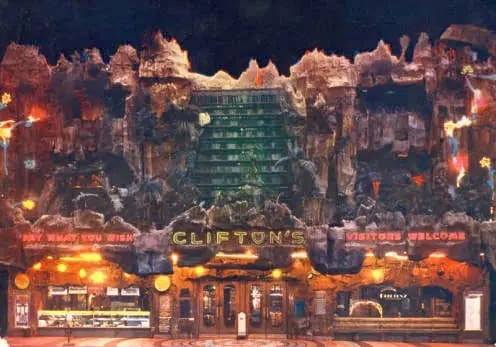

But if you are really after comfort, walk to Clifton's Brookdale on Broadway. Partake of its sylvan fantasy and sit down on the miniature mountain. Watch the "limeade Springs" bubble by you. Here you get a good view of both the neon cross perched atop a tiny chapel and the moose head upstairs which stares back. There's usually entertainment on weekends. On my most recent visit I had macaroni and cheese, beets in Mayo and flan as a woman sang Spanish ballads accompanied by a man with a Casiotone. Others, who knew the songs, ate and clapped along.

But the cafeteria isn't always wholesome. According to "cruisingforsex.com" the toilets downstairs are "cruisy"– people meet in the Robinsons May department store and walk down to the cafeteria because "it's safer." I cannot back this up with personal experience.

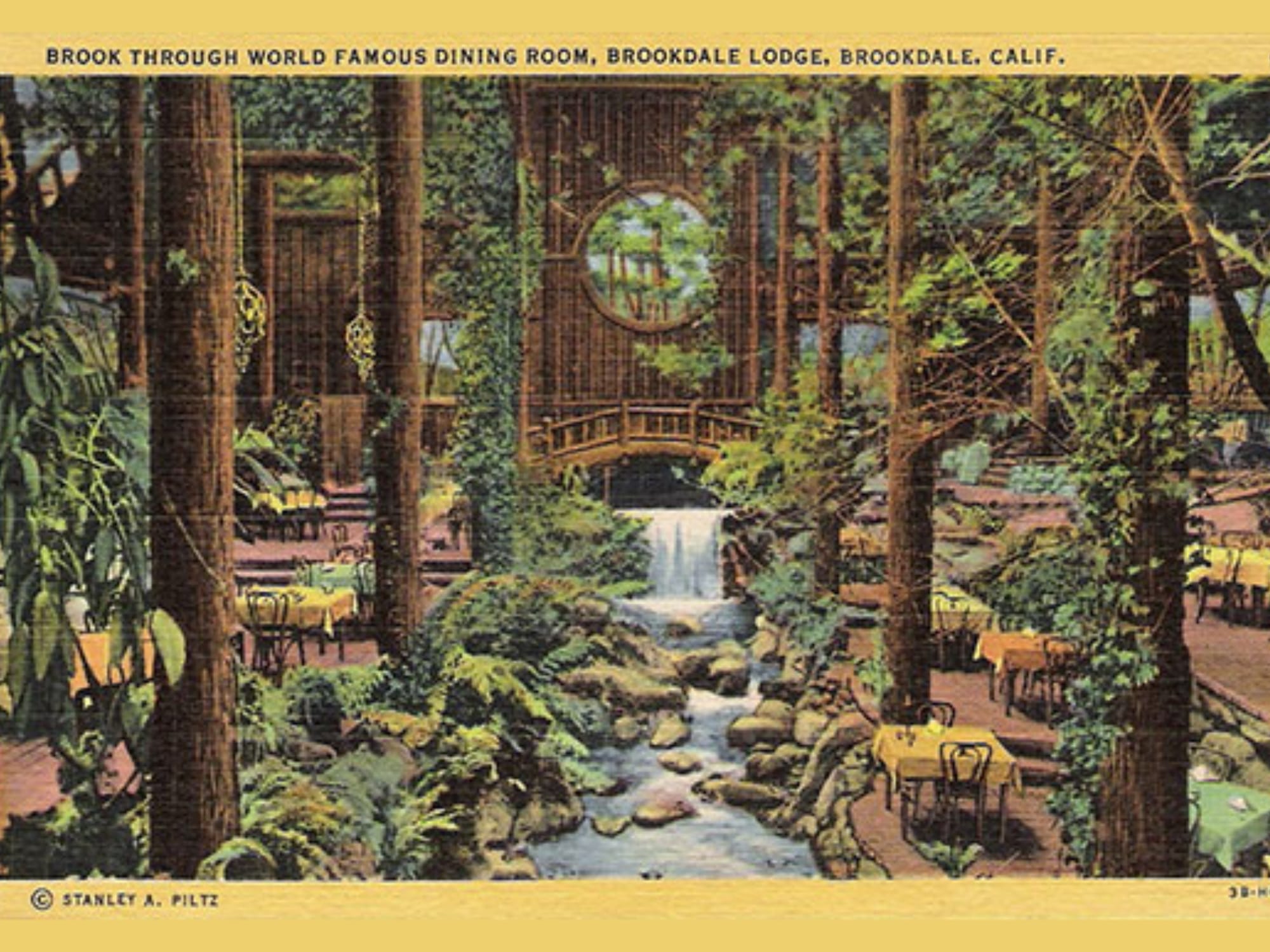

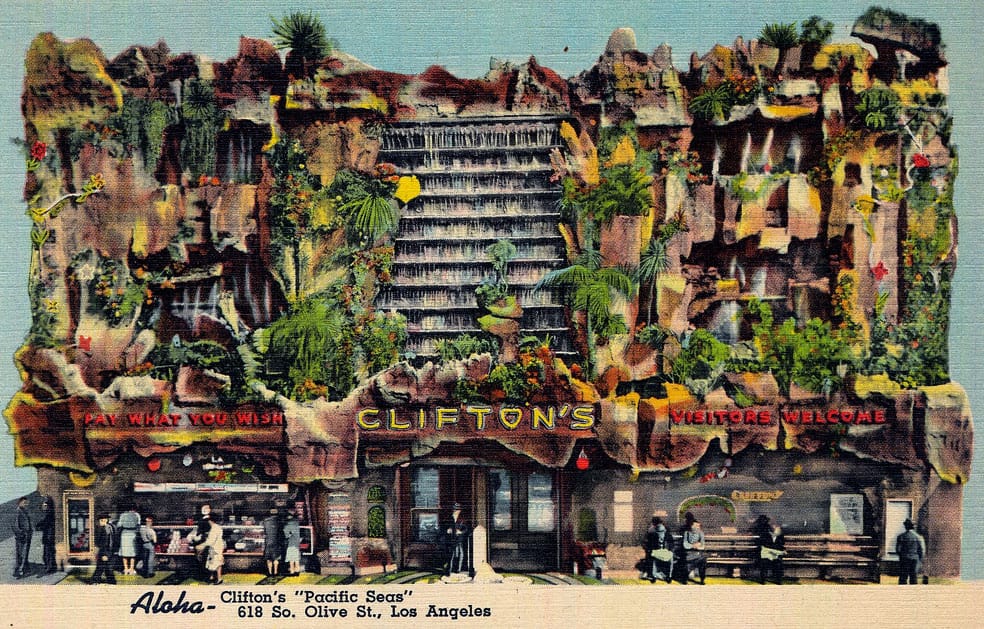

This is not the first Clifton's. The original "Pacific Seas", built in the 1930's by Clifford Clinton, is now a parking lot– the intricate tropical façade with waterfalls and tropical foliage and sign reading "Pay What You Wish" are gone. But what a cafeteria it must have been. If only I'd been alive to see the Polynesian interior with real canaries, neon palms and a "rain hut" with showers every twenty minutes. Where else in the world could you eat chipped beef in such splendour?

My favorite Clifton's, the Silver Spoon, almost thrived underneath the Orange Smoggy awning at 7th and Olive until it was closed in the late 1990's. While not as dramatic or beautiful as the Bradbury building, it was one of my favorite places. It had soul, and now it's gone. Clifton's moved there in the early 1970's, though the building dates from the twenties.

The sign outside read, "The line from the door to the register takes about eleven minutes, but it's worth the wait!" There was never any line when I went, only a few employees and elderly patrons. The old mahogany display cases were kept intact, and downstairs they were filled with old world knick knacks, ceramic ale mugs, pastoral-scene plates, and little clogs. Upstairs in the employee break room, the cases were untouched since the building's jewelry store days. The cases displayed yellowed illustrations of earrings, chokers and bracelets, sending off black-penned rays of light. [How did I get in there? My younger self was intrepid. I miss her.]

The place just got stranger on the lower level, or "Soupeasy," which featured a "The Garden, a Quiet Place for Meditation," a hold over from the Pacific Seas location. This Garden was so quiet, you needed a token from the cashier to enter. Once inside you got a glimpse of a bench and glass case. On shutting the door you're enveloped in darkness. Eventually, the lights in the life-sized diorama come on, illuminating a wax Jesus praying in Gethsemane. A disembodied voice, just like the nasal voice in a newsreel circa 1940 begins, "In these troubled times, many have died in war, but we live...many are homeless and hungry, yet we are fed and sheltered..." And one can't help think that just outside the streets are filled with Angelenos—some are refugees, immigrants, and the displaced who've fled from poverty and their own war-torn countries, now meandering through the vendor's stalls on the street above.

How strange to sit there listening to the sanctimonious voice, just after eating a meal of macaroni and gelatin, watching the colored lights illuminate Jesus in red and green, and not see it as funny. How strange to understand the innocence of the whole project, to be in that optimism, as the yellow light turns on the head of Jesus and the speaker closes, "Like Pontius Pilot, every man must ask himself, 'What shall I do?'" And you are left in the dark to find the door.