DIY, Riotgrrl, and Writing the Sick Body

my life in zines

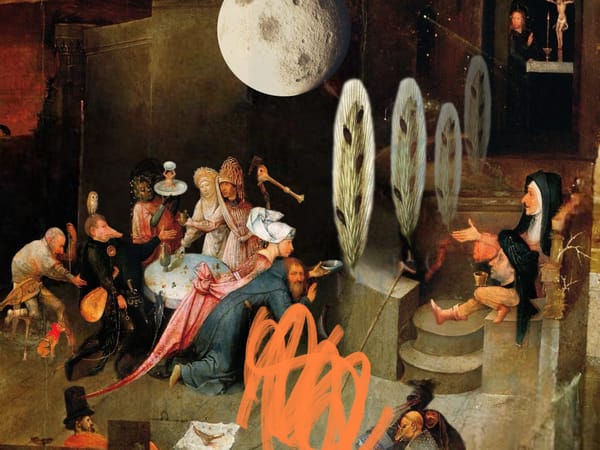

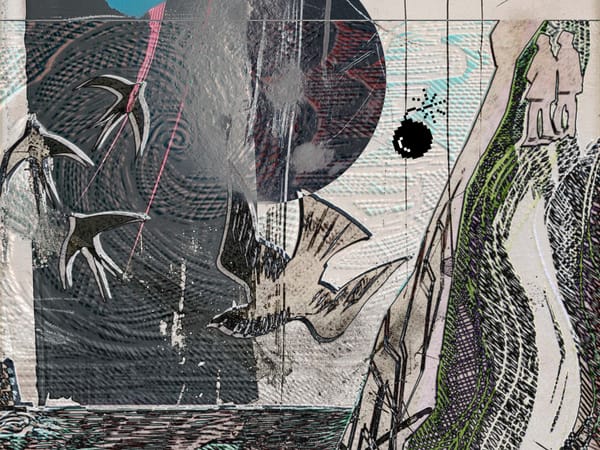

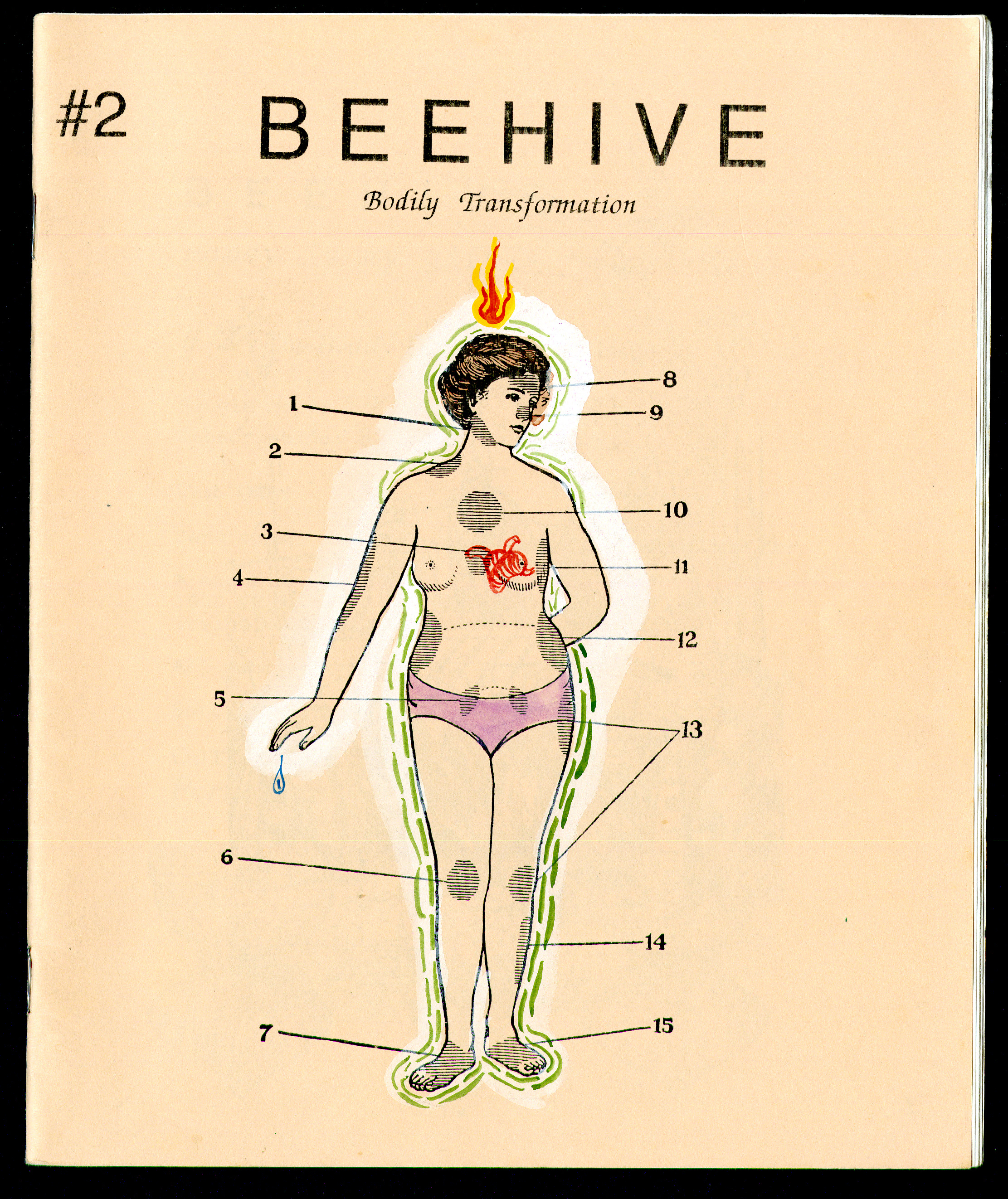

Picture it: a photocopied wonder cabinet of savoury aspics on a bed of iceberg lettuce, the amorous whispers of nuns, vulvic martyrdoms and naked deep-fakes done with X-acto knives. This is Beehive, the zine I created with artist Laura Splan which will feature in the Brooklyn Museum’s upcoming show Copy Machine Manifesto, along with a video poem born out of the same collaboration.

The images are both a harbinger of future life with chronic illness and an ownership of a sick past, a reclamation of the othering that happens when ones body is medicalised or transgressed by violence

Beehive was a hand-collaged, Xeroxed kaleidoscope of camp food prep and arcane diets, kinky religious iconography and antique gynaecological diagrams interspersed with poetry. Our zine marshalled the vision of our artistic community—feminist queers working in and around Los Angeles in the 90s.

In making a zine you become a collector of texts and images, cutting and pasting in new contexts and juxtapositions, adding in your own voice and gestures, laying them out around the found work so that one speaks to the other. In hindsight, I can see it’s pretty good training for writing an extensively researched creative nonfiction book of feminist reclamation like Ashes and Stones. Writing A&S involved cutting up drafts and research notes and laying them out on the floor, just like I did with the elements of Beehive. Unlike my recent work writing Ashes and Stones which was born out of acute isolation, Beehive was made in community. Riotgrrl was happening around us but I was not a girl anymore—remote from that rebellion—not a fan but instead a radical poet happily subsumed by the goings on.

“Beehive is a zine about the intersection of ideas, about ambivalence, power and desire.” —from Beehive, no. 1.

In 1993, I worked in a university medical library and poured over the archaic tomes full of obsolete medical practices. I had access to a Xerox machine, as my job included copying excerpts for inter-library loan. I collaged these images from obsolete medical texts on thin wood panels called ‘door skin’, painting in gauche and oil mixed with waxes. All but one of these paintings were incinerated while I was hospitalised. I had been using the University of California Irvine’s painting studio on the fly while enrolled as a Humanities grad student, painting the panels in the vacant space late at night. My work was confiscated and destroyed.

My practice had to survive on a smaller scale, and this was possible with zines, something I’d created a lot of as a punk teen in the 80s. I began making zines in high school because I wanted something to trade, answering ads from the back of Flipside and Maximum Rock & Roll. Zines were always about community. This was a way to make contact with others—trading mixed tapes and little Xeroxed rags through the post.

For Beehive, I took the cut-and-paste rebellion of my teens and infused it with my creative practice as a painter and poet. Working with Laura, we opened it up to the community. Biomedical imagery appropriated and re-contextualised in collage format was not an intellectual exercise for me but a personal exorcism born of lived experience with multiple, severe chronic illnesses. It is painful to look back at these tortured images where the subject is clearly objectified by the (male) medical gaze. I realise now that they are actually proxy-self portraits.

Last week I received an email invitation to the opening celebration for the Brooklyn Museum show. For months leading up to this, I hoped I might be invited, and I imagined going—how many times in your life will you have a zine you made in your 20s in a museum in New York City? Would anyone who contributed to the zine be there, and would we recognise each other? It won’t happen; I don’t have enough cash to fly from Orkney to New York, but it was nice to think about what it might be like to be part of things.

Having work in the Brooklyn Museum show feels weird, maybe a bit posthumous. The zine and short video poem are DIY works re-contextualised without any direct involvement or consultation with me. Initially the curators found the zines in a library archive, attributed only to Laura. I had been removed by the archivists or simply omitted as a co-creator of the work.

To those with institutional power in the art and publishing worlds, it’s as if I’ve come from nowhere, a middled-aged woman crawling up from the unknowable depths of obscurity into the hallowed spaces of culture. I’ve been making work for decades, so why do I feel like I’m gate-crashing? In my darker moments I think it’s because I’m disabled and working class, and I don’t see many people like me who make it this far.

There are big gaps in my art making and writing over the last 40 years. My CV falls apart like a badly-glued collage. The missing bits are points where I couldn’t make work. I was taking any job I could get because I needed money in between years of living the medical hell depicted in the corners of Beehive. The images are both a harbinger of future life with chronic illness and an ownership of a sick past, a reclamation of the othering that happens when ones body is medicalised or transgressed by violence.

Beehive was also full of deeply personal stories I believed about myself and my body that I now know are wrong. This clarity is one of the benefits of survival and aging. At the same time the zine was proof of a lush and vibrant queer community all around me. It didn’t last, but how could it? At the time, I thought it was nothing compared to the freedom and the queer validation I knew in San Francisco in the late 80s. Here we were in SoCal for a glorious moment, creating a pocket of safe space while plotting our separate escapes, leaving behind ephemeral bonds in copy paper and rubber cement.