Eyries of the (Other) World

—ossuaries I have known, an ongoing series—

PART II of The Tomb of the Eagles

This post continues my exploration of the Tomb of the Eagles in Orkney. Become a paid subscriber and read the first instalment here.

“Satisfied [the skeleton] contemplated the Milky Way, the army of bones that encircles our planet. It sparkles, glitters, shines with all its myriad little skeletons that dance, jump, turn summersaults, do their duty.”

—Leonora Carrington, The Skeleton’s Holiday

A stone house

is a skin boat

is a hazel basket

is an eyrie

is a nutshell:

is earth--

is sky

in a skull.

What was life like for the ancestors living in Orkney thousands of years before me? Anthropologists writing on the Neolithic people of Orkney have found a relationship between their skin boats and their houses. The vessels probably resembled oblong coracles, or small round bottomed boats often transported on the back, like turtle shells when not in the sea. The shape of their stone dwellings was also oval. Garnham in his book, Lines on the Landscape, Circles in the Sky, suggests these rounded shapes were based on early baskets, woven from native Orcadian willow or hazel. In weaving a basket, one begins with a cross which becomes a spiral and then a three dimensional open sphere--a meditation on dimensional shifts. The supple material hardens into a rigid container for life-giving stuff: limpets, sea coal, hazel nuts.

Might these early basket weavers have watched birds building nests? Perhaps the sea eagles were some of the earliest teachers or, in the parlance of our times, tech consultants? The eyrie of the sea eagle is built over years and even generations, some nests measuring two metres across and one metre deep—about the size of a coracle. The first people to live on Orkney migrated in this style of skin boat, and the majestic sea eagle greeted their arrival.

Sea Eagle as Psychopomp

‘They provide first council, guide the first step of the newly dead, who are wretched in their abandonment, like the newborn.’

—Leonora Carrington, the Skeleton’s Holiday

Bones of carrion birds were found among the human remains in the Tomb of the Eagles in Ibister on mainland Orkney. Crows, short-eared owls, kestrels, and—incredibly—over 500 sea eagles lay side by side with ancestral bones in the foundations of the tomb built in 3200 BCE. The eagle remains are also mixed in with human skulls in the chambers. The tomb was in use for 800 years before it was finally decommissioned and blocked up with rubble which also included 215 sea eagle bodies. The eagles were not used as food; the remains had not been butchered but were interred whole as companions of a kind—a totemic animal to the people buried inside.

Mircea Eilade’s seminal work on shamanism describes totemic bones as a representation of the ‘inexhaustible matrix of life.’ Dominant Western culture sees bones as a symbol of death. But the findings in the tomb suggest the earliest Orcadians may have believed the bones contained a storehouse of spiritual information and presence.

In Shamanic tradition, the spirit that guides the dead to the next world is called a psychopomp. The dead transform from the person they were in life into a bone object and an ancestor. This journey is not done alone. The liminal space between the living, fleshed out person and a totemic bone is overseen by a spirit-agent. The structure of the Tomb of the Eagles suggests a mortuary ritual (I talk about this in Part I) now known as sky burial. In the case of the Tomb of the Eagles, this spirit-agent is sea eagle—both a carrion eater and apex predator.

Sea eagles can live for four decades—approximately the same lifespan as our ancestors buried in the tomb. With a wingspan of over six feet wide it appeared as a mighty– perhaps even angelic–messenger.

Sea eagles were once persecuted in Britain; the bounty on their heads was six shillings at the start of the 18th century. They became extinct in Britain one hundred years later. The myth that they were competitors for fish and game as well as a threat to lambs led to their eventual decimation. The sea eagle has been reintroduced to Orkney, but they remain under threat by pesticides. Sea eagles have the highest concentration of DDT of any European raptor. In other parts of Europe, lead and mercury poisoning have been found in near fatal levels in sea eagles.

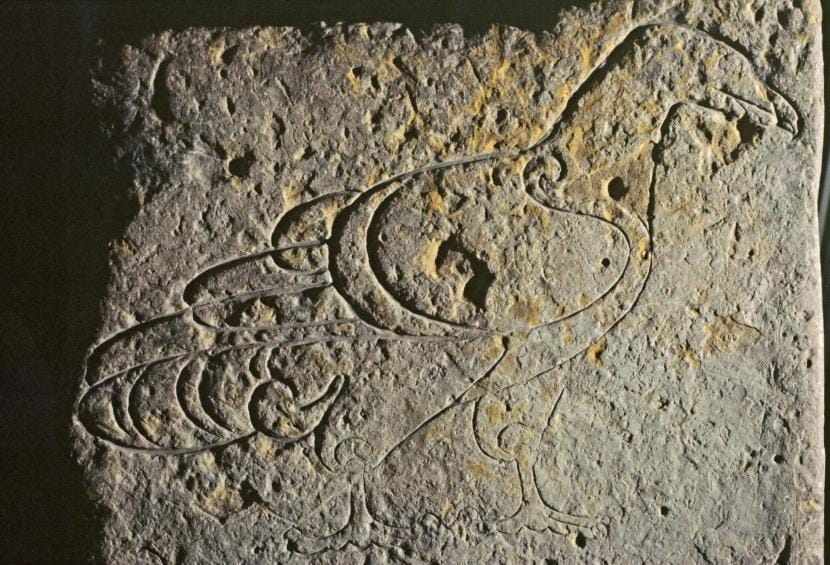

The sea eagle remained a sacred animal, even to the Iron Age Picts in Orkney, as this Pictish carving from Orkney attests.

The Norse settlers on Orkney would have known tales of the great sea eagle sitting atop of the world tree Yggdrasil. Perhaps they would have heard a version of Hjálmar’s Death Song in Orvar-Odd's saga or a similar story told in the Kvæði ballads of the Faroe islands.

“Flies from the South the famished raven,

flieth with him the fallow eagle;

on the flesh of the fallen I shall feed them no more:

on my body both will batten now.”

[translation from Sacred Texts]

Hjálmer fights a duel over a woman, and the feud turns into an all out kin-battle. As he lays dying, he sees a hungry sea eagle flying with a raven from the south. He laments that he’ll no longer feed them with the corpses of men he has slain. Now his own body will be their feast.

The Norse settlers on Orkney would have also known stories of other bird-psychopomps. Valkyrie means ‘chooser of the slain.’ Valr in old Norse is a carrion bird but also those slain in battle. Valkyries carried the war dead to Odin’s hall, Valgrind (“hawk-gate” but also “slain-warrior gate”). Freya, The Old Norse goddess of love, war, and trance magic also acted as a valkyrie. She had a valshamr—or raptor shape—often referred to as a cloak.

Several thousand years after the Tomb of Eagles had been blocked up with rubble, the cosmology seeded inside the cairn still ranged around the lives of the islanders, taking flight over the cliffs and hollow hills in the form of goshawks, hen harriers, ravens and sea eagles.

A Tomb Bathed in Light

“The skeleton’s lodgings had an ancient head and modern feet. The ceiling was the sky, the floor the earth.” —Leonora Carrington, The Skeleton’s Holiday

A few years before I visited the tomb in 2007, Ilse Babette Barthelmess, a Berlin-born professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology, embarked on a profound project of experiential archeology. For years she met the sunrise inside the tomb, calculating its rise and fall in relation to the entrance. She blocked the modern skylights in the tomb so as to be in full darkness. She woke in the bleak winter and trekked there through the snow. She watched her shadow form on the stone walls in the full summer sun as light flooded the interior. This work culminated in a ground breaking work of poetry, art and conjecture—a book called A Celebration of Sunrise at the Tomb of the Eagles: a journey between exterior reality and inner vision evoked by a Neolithic cairn in Orkney.

Barthelmess begins by flying over the cliffs in a hired plane. She sees the cairn from an ‘eagle’s eye’ view, where the entrance of the cairn faces the sea.

“Here, where wind, water and rock meet in a fierce embrace, Neolithic people created a sacred space to rest the bones of their ancestors. Was it more than just a tomb: a temple to worship the eternal cycles of life and death, light and dark, song and silence?” —Ilse Babette Barthelmess

Much academic archeology shies away from conjecture regarding the spiritual realities of the people it studies, but Barthelmess, like myself, isn’t bound by these conventions; there’s no need to dismiss mysterious finds as ‘ritual objects’ or structures as having a vague ‘ceremonial’ purpose. Unbound, we go deeper—finding further questions. Barthelmess’ discoveries are subjective, authentic and have the ring of truth to them.

Barthelmess found a spring burbling down the slope of the ridge where the tomb was built. She wonders if perhaps this was a substantial source of freshwater 5,000 years ago, before the ground behind the tomb was drained. After doing extensive research around sacred wells in Yorkshire, springs signal meaning for me—every weeping, life-giving, sweet water source marks out what was once a sacred landscape.

“Many a time I have sat inside the tomb, motionless, and have listened intently, wondering whether a faint ‘drumming’ could be heard penetrating the rock.” —Ilse Babette Barthelmess

The wind and sea in Orkney are percussive—the landscape amplifies and changes its fierce weather-song. Within the tomb, surrounded by the natural amphitheatre-like ridge facing the sea, the effect is operatic and otherworldly. Barthelmess found that on certain clear days in late April and mid August, a channel of sunlight from the horizon over the North Sea points straight into the tomb, like a golden road.

“I found a noisy crowd of seals assembled on the steps of the pyramid-shaped rock below the cliffs…On sunny mornings from inside the tomb I heard them singing, bubbling, snorting, howling, and an air of great enchantment pervaded the place.” —Ilse Babette Barthelmess

Mornings in the summer, the sun illuminates the interior of the tomb, giving light enough to work. Did this design enable the sacred ordering of the bones within? A number of intentionally broken pottery fragments lay on the back wall where the sun falls. Like the more famous chambered cairn in Orkney, Maes Howe, this is also a celestial observatory, once a working temple—a metaphysical machine of symbol and spirit.

Barthelmess concludes that the tomb lay in darkness for 8 1/2 months of the year, roughly the time of gestation for a human infant. Perhaps—and this is my guess—this also parallels the duration of excarnation, the time it would take for the bones of the dead to be cleaned by the elements and the eagles. The three and a half months of illumination allowed for ritual inside the tomb, for the people do the work of burial and birth in their community, in time with the course of the sun through the tomb.

All burst into bloom and decay

--"Eyes of the World," The Grateful Dead

Charlie Girl was a name given to a young woman's skull found in the Tomb of the Eagles. Charlie Girl is a bit of bone and a lot of guesswork. In her short life, she had another name, a name given to her at her birth in late spring when light bathed the bone house, the place where she would be buried.

She didn’t remember any of this and had to take her people’s word for it. An important thing had happened when she came into the world. She cried with her first breath as the dead assembled. The weeping was for her as well as the new ancestors.

Years pass around the cliffs, around this cycle of birth and return. Parts of her survive long enough to be (mis)understood.

Her skull shows an indentation at the centre, the bones of her neck marked by the thickened ligaments attaching wide muscles. She has osteoarthritis in her ribs on one side: she carries heavy loads using a strap around her head and beneath her armpit. Charlie carries her world—grain and seaweed and nuts–in a woven willow basket. She carries rocks, perhaps to the tomb itself. She drinks barley ale boiled up with hot stones in earthen pots marked with a thumbnail. She wears a few limpet shell rings on a strap around her neck. One day she finds a piece of jet in the surf to carve and polish into a button.

The sun pierces the tomb in the summer months as the bone-gatherers form the dead into neat piles. They work by the light of the glowing beam through the passage. Someday Charlie Girl will be one of them–gatherer, bone, ancestor. She hears a whoosh of eagle wing, a percussive scream over the dark tide below.

Further reading:

https://www.tomboftheeagles.co.uk/

Crowdfunding campaign for the Tomb

https://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/p/tomb-of-the-eagles

Article in The Orcadian

https://orcadian.co.uk/campaign-to-re-open-tomb-of-the-eagles-moves-a-step-closer/#google_vignette

Garnham, Trevor. Lines on the Landscape, Circles from the Sky: monuments of Neolithic Orkney. Tempus Publishing, 2004.

Hedges, John W. Tomb of the Eagles: A window on Stone Age Britain. John and Erica Hedges, Ltd 2000

Barthelmess, Ilse Babette. A Celebration of Sunrise at the Tomb of the Eagles: a journey between exterior reality and inner vision evoked by a Neolithic cairn in Orkney. Orkney Museums and Heritage. 2004