Haystacks & Hearth Goddesses 🌾

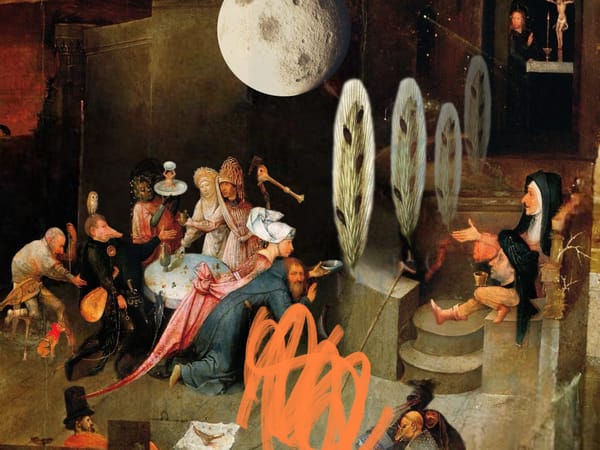

a Lammas-tide Kaleidoscope 🌚

This is part of a series of irregular posts for paid subscribers—sketches for a book I thought I might write about Orcadian women accused of witchcraft.

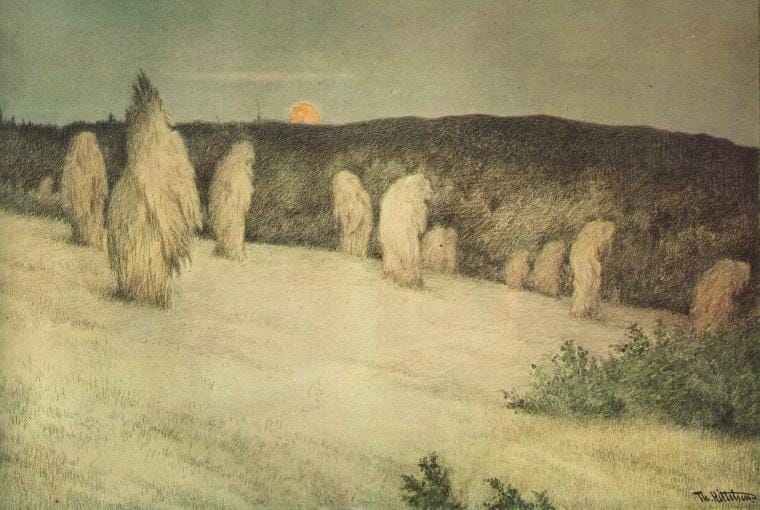

When are haystacks not really haystacks? This image by one of my favourite fairy tale illustrators, Theodor Kittelsen, was brought to my attention by @NeuKelte on Mastodon. Kittelsen illustrated Norwegian folktales, and in his work much of the landscape is anthropomorphised and uncanny—the land is a troll and the troll is a land.

These haystacks just up going for a stroll in the gloaming of an evening are the stuff of folk horror, a genre where anything that smacks of ye olde ways is sinister, and all things antiquated and rural equal creepy. I love that feeling of the uncanny, but there is a risk, always, in horror that we damn the things we most love. Who are these haystacks, and why are they so creepy?

Lillias Adie’s forced confession claimed she first met with the devil in the hour before sunset on Lammas behind a stook, or bundled sheaf set up in the field to dry

When I was writing the final draft of Ashes & Stones, patterns emerged in the confessions of those accused of witchcraft. Why did the accused so often describe the so-called devil as someone looked a lot like Odin? What does the rallying cry horse and hattock really mean? And what’s with all the satanic haystacks?

I figured some of this stuff out, thought much of it was too detailed, too much of a diversion to be included in the book. I discovered a lot of answers after Ashes & Stones was published, but some things, like the haystacks in the confessions, remained a mystery—UNTIL NOW. It’s a Lammastide revelation, to be sure.

When I think about folklore, it’s always in a constellation of sense-making rather than a deliberate linear argument. It is an opening out of meaning and metaphor rather than an academic sort of closing down. Sometimes it involves travel—let’s call it besom-flight—both geographical and metaphorical.