Just Don't Mention the War...

Full circle on the full cold moon 🟡

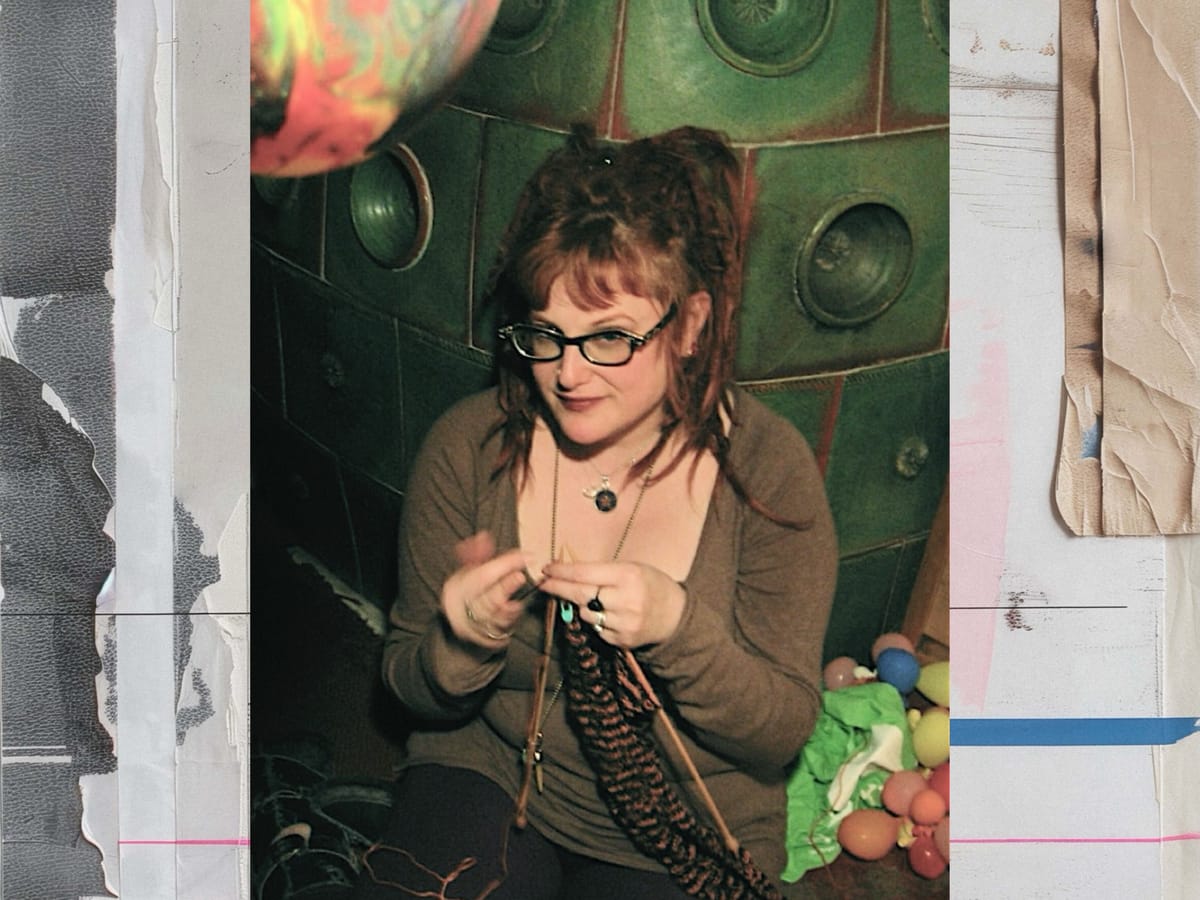

At the full moon I revisit older work. I wrote his blog post almost twenty years ago as I travelled around Bavaria. It feels relevant now as we face a rise in the far right in Europe and the US. In the post I still refer to the US as ‘my country.’ I had not yet adopted the UK as home. When I wrote this, I had just been travelling with friends who were installing an art piece in a small town in the Netherlands.

Unless one lives and loves in the trenches, it is difficult to remember that the war against dehumanization is ceaseless. —Audre Lorde

Two weeks in Bavaria was definitely not part of the original plan, but things have conspired against us. Through the generosity of our friend N, we have a place to crash in Munich and he's been showing us around, driving to many Bavarian breweries where I've been sampling all the dunkel beer I can find.

In Bavaria everything is meat. I've been living on salty pretzels and beer and now my extremities are swollen from water retention.

Missives from the Verge with Allyson Shaw is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

E is back in the Netherlands at the University of Utrecht. B and I will be joining her in less than a week. Apparently on her way to Utrecht via train someone threw themselves in front of the tracks. As she was in the first car right behind the driver, she saw the driver go into shock. This must happen a lot. When M and I were traveling to Vienna someone threw themselves on the tracks and I felt the carriage go "bump".

Earlier in the week, we trudged up the mountain to Neuschwanstein, the inspiration behind Walt Disney's "Sleeping Beauty" castle in Disneyland. I'd already been to both the original schloss and the California ersatz version. I preferred Neuschwanstein the first time I saw it, when winter fog softened its static 19th century edges. It’s late summer and there are so many tourists. I bail on the tour. While everyone else goes inside, I wait and watch the stream of humans go in and out, many of them American or Japanese tourists in bright, casual clothes that make them look like children. Some wear the jaunty Tyrolean hats sold at tourist stalls. I consider buying one because I think they are cool, but I don’t. There is no way to decontextualise them from tourist tat, and I worry they mean something I don’t know about.

Stern conformity hangs heavy over Munich, despite locals' insistence that "the past is history" and that Bavaria is part of a tolerant, modern EU state. The uneasy pact with the past is felt everywhere, and this brutal history of the Third Reich’s rise to power is too similar to my own country’s march to the right.

Americans are notoriously ignorant of even their own recent history. In school, history stopped at the Nazi invasion of Poland-- the summer would come before we ever got to the hydrogen bomb, the Korean War or Viet Nam. One person my age I met in Munich said she was too young to remember the war, so why talk about it all the time? But how can I not think about it when my own government cynically uses the holocaust and the "good war" as a metaphor for their bloody and bankrupt foreign policy?

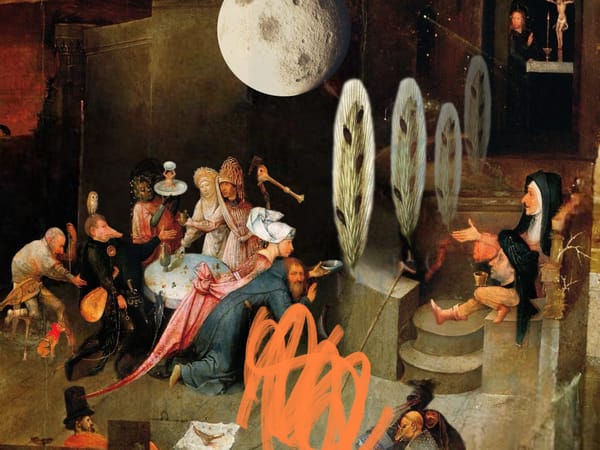

We go to the Haus der Kunst and I’m amazed by the architecture-- the old glass building rebuilt in a heavy neoclassical style by Paul Ludwig Troost. It was modelled to Hitler’s vision, himself a mediocre painter. Pictures of the Degenerate Art Show hang in a corridor by the toiletten. The exhibition held in 1937 contained hundreds of modernist works of art confiscated from German museums. Hitler claimed the work was an insult to Germans and lacked proper skill in execution. This aesthetic cleansing was part of a larger culture war that began with book burnings. The initial purge was one of art and ideas. [My current self asks if this is not now being done in myriad, insidious ways in the US and elsewhere?] The images hung by the toilets reveal the Nazi's invented mythology of hatred. Their extensive othering of ideas and aesthetics—anything modern and challenging—proceeded their deadly project of the purging of people. [Or the two were simultaneous.]

At the entrance to the museum—also the exit—iron doors and massive columns support the roof's stark planes. The design of the Haus der Kunst gives itself away—insisting on the past even through reinvention. Ivy once tried to grow over the surface, leaving dead veins over cold stone.

The Haus der Kunst is showing master carver Georg Petel's Baroque sculptures of crucifixions and meaty Saint Sebastians. I assume he was working from corpses, rendering the tortured bodies in obsessive detail in wood and ivory.

What is the difference between bearing witness to suffering and perverse sentimentality? Can we understand the suffering of others without replaying it in detail? [It is worth noting I didn’t visit Dachau in part because I couldn’t answer this question.]

I sit watching the Gilbert & George video installation in the museum. It’s a preview of their show at the Tate Modern in London. It’s in English, and as I listen to them finishing each other's sentences, I’m surprised at their sincerity. Why do I think they would be ironic and distant, speaking in riddles? Gilbert is Italian but has been with George in Spitalfields for 40 years now. They are Londoners, and I understand their work now because I, too, am a Londoner.

We are in a little house in Rieder in the Bavarian countryside with my friend N. After the war, this house sheltered men coming home from the front, wanderers lost in the chaos after surrender. I imagine where they might have slept in the tiny house, what stories they told, and which they withheld.

We cook on the wood burning stove and watch a cat stalk through the grass. Everything is green and lush outside. Cows luxuriate in the fields, their bells ringing. Poppies nod in the wind and still I think of war. Peace is surreal. I wonder about the ambiguity of this place--idyllic and terrible—so near Dachau. N is full of stories from the woman who grew up in this house. She said that after the war all the children ran around wearing red trousers. Their mothers had cut up the Nazi flags and used them to make clothing. Got to use them for something.

Missives from the Verge with Allyson Shaw is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.