My Own Personal Psychopomp 😵

revisiting the work of artist Mike Kelley 🌝

I’ve returned from my pilgrimage to London to see the Mike Kelley show, Ghost and Spirit at the Tate Modern, and I’ve recovered enough to process it.

A couple of days after Kelley’s death by suicide in 2012, I wrote a blog post which I revisit here. He was 57 when he exited, just two years older than I am now.

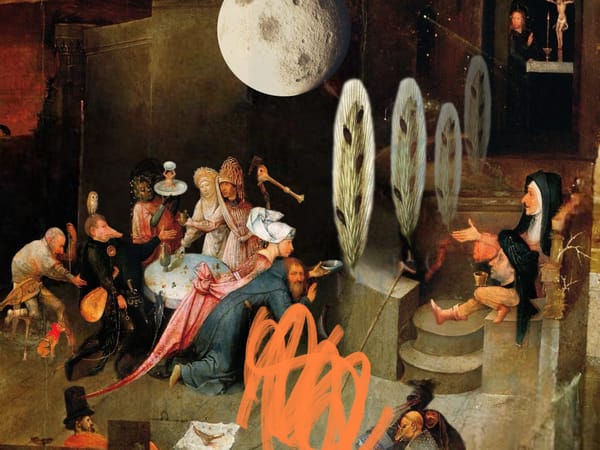

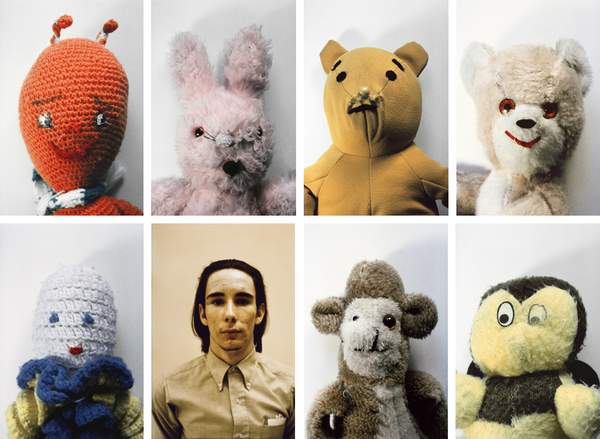

Most people know Kelley’s cover for the 1992 Sonic Youth album, Dirty, which frames forlorn handmade animal dolls in formal portraits along with Kelley’s youthful visage. Similar plush toys wound together in a monumental panel, suspended orbs, or situated alone on blankets defined Kelley’s work in the late 80s and early 90s. This work was received with the full force of biographical fallacy—critics assumed Kelley was making work about his own childhood trauma when really he wanted to talk about disposable consumer culture; he was in dialogue with feminist artists working in craft mediums.

Kelley went on to embrace the autobiographical misunderstanding of his work as a direction, and much of his larger scale work of the early 2000s is about repressed memory, popular culture and shared trauma.

It’s hilarious and still full of pathos. A trickster figure in an art world that takes itself too seriously, Kelley remains one of my teachers. (Though I feel I am not ‘allowed’ to be funny, given the subject matter I write often about and atonal nature of writing online, but I digress.) Too many of my teachers—Plath, Sexton, Woolf and Kelley—have killed themselves. As I perch in yet another dark night of the soul, I wonder what this means to my own life.

I lingered in front of his most well known work, the tapestry of found handmade objects titled More Love Hours Than can Ever Be Repaid. It features not one but two yellow macrame owls, and a crocheted alligator that has remained with me all these years. The whole thing is festooned with that staple of American midwestern decor—sheaves of rainbow corn. Here is a visceral return to the tactless grottos of my 1970s childhood: beautiful, gross, paltry. I went to the show with two friends, one who grew up in the UK and the other in Canada, and all three of us related to the wax candle sculpture, The Wages of Sin. We knew these 70s-80s ornately crafted candles by heart even if we had never seen them before.

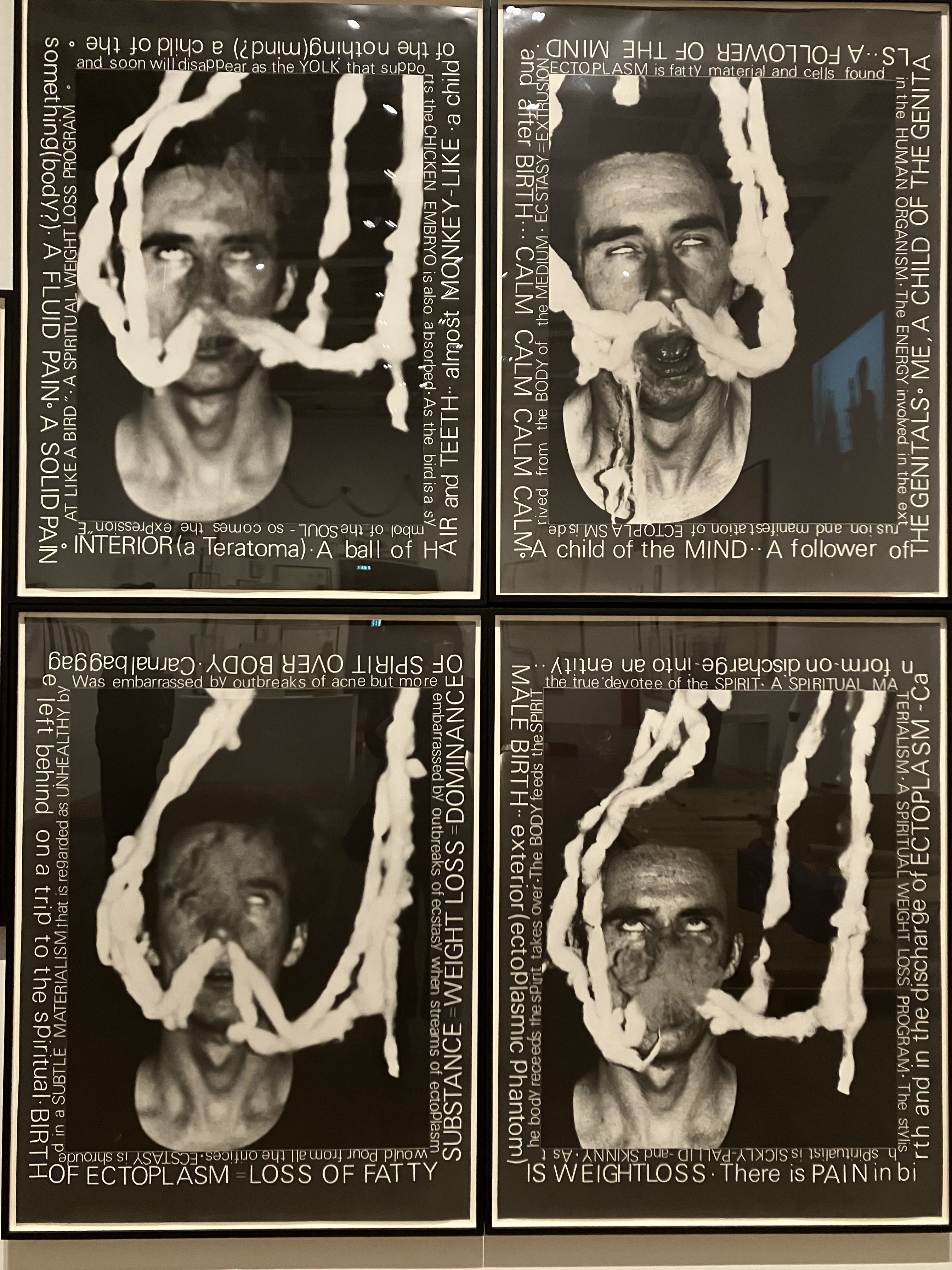

Kelley deconstructed the aesthetics of hysteria, mysticism and nostalgia. He marked out the absurdities of patriarchy and toxic masculinity and made them hilarious.

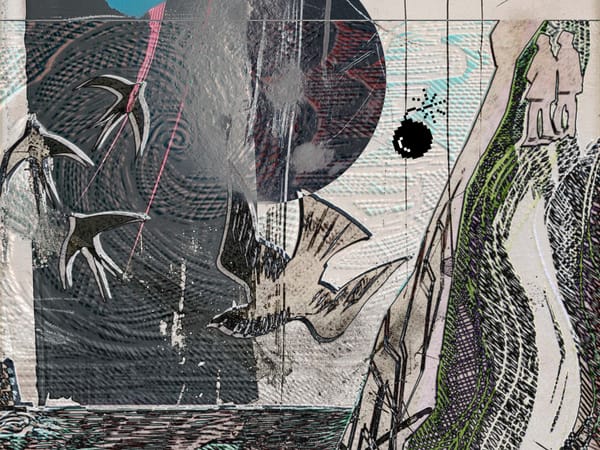

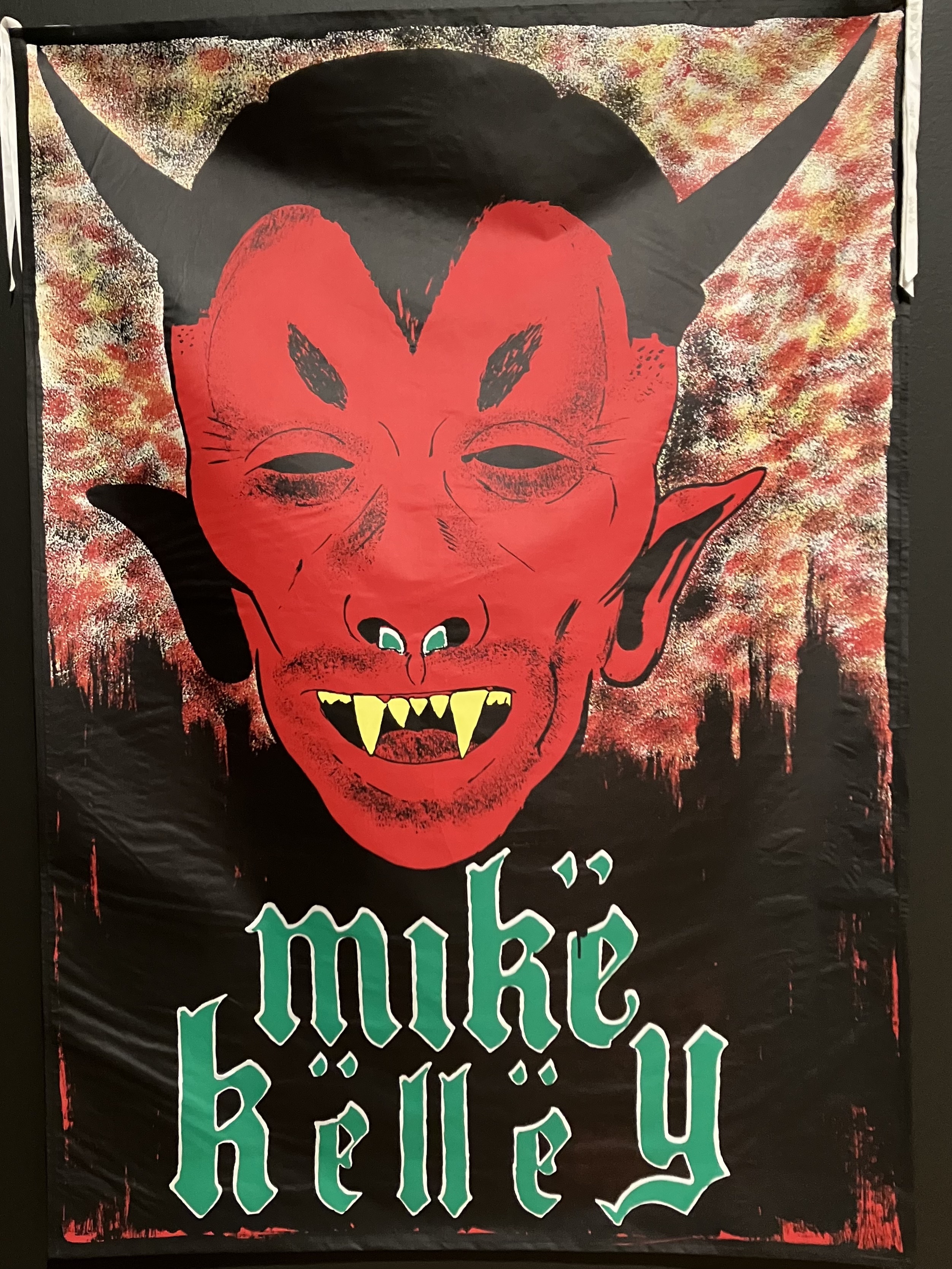

Seeing the work in the austere, high ceilinged Tate, I was struck with how low brow it felt: here were drawings that look like they were made with shit, Rat Fink demons cavorting, adolescent doodles and bad tattoo art writ large on flags.

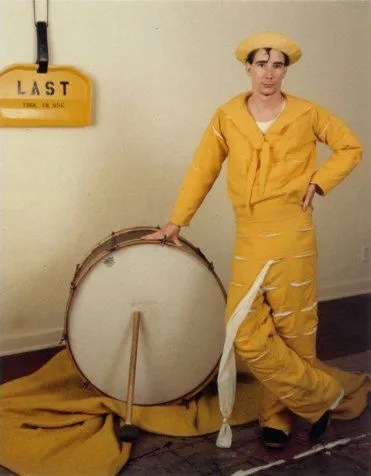

When I first saw his work as a wayward teen, I felt as if we—he and the viewer—were in on some great prank. We were getting away with it because I got the joke. Kelley’s midwestern accent sounded like home. We both grew up in the suburbs of the American Midwest. Kelley’s Banana Man, a video performance of existential angst where Kelley, dressed in a yellow sailor ‘leisure’ suit covered in pockets, tells a story of slapstick woe. Banana Man is tied in my mind to Chicagoland TV legend Ray Rayner, whose 1970s children’s morning show featured cartoons, crafts, corny jokes and leisure suits. I saw Banana Man in 1988 and had a revelation: if I lived in a world where this art could happen, it meant I was free of all the dumb shit I’d been made to carry as a girl. Here was all the permission I needed.

In the Tate show, Kelley’s birdhouse ‘spirit collector’ sits under glass like a specimen. The howl & drum of sounds from his shamanistic ritual performance at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions space plays over it. In this room, his early work is reshuffled, creating a ghostly feeling that wasn’t there initially—adding dimension for a world still mourning his passing.

(I once exhibited my work at LACE, but it was so long ago. Unambitious thing I am, I never wrote that stuff down, and now can’t remember which piece it was. There was still a pang of what-might-have-been watching LACE’s interior projected on a wall in the Tate in London).

As an older woman revisiting this work nearly 40 years on, I now see Kelley’s sincerity, something I didn’t pick up on as a young woman. The Tate curation is apt and bittersweet, framing his work as ghost narratives.

My favourite pieces in the show were the Kandor jars. (What is it about THINGS IN JARS? something else to unpack…) In the Superman comic, Kandor is the lost city from Superman’s home-world, shrunken down and preserved in a bell jar. Kelly creates myriad lurid and inviting versions of the tiny city. In a companion video piece, Superman Recites Selections from ‘The Bell Jar’ and Other Works by Sylvia Plath (1999), a square-jawed Superman, played with grave earnestness by Michael Garvey, recites excerpts from Plath. Plath was an American immigrant in the UK and knew well the melancholy of lost home. The Kandor jars are iterations of the cliche ‘you can never go home again’—illuminated by a wonder particular to childhood and adolescence, or at least what we remember childhood to have been.

Are my own memories of Kelley’s work and his fleeting presence like some candy-coloured resin kingdom, aglow with loss?

The Tate show ends with Kelley’s video Bridge Visitor (Legend Trip.) A legend trip is a teenage rite of passage involving urban folklore pilgrimages to creepy sites—the starting point of many 80s horror stories. In many ways Ashes & Stones was a six-year legend trip…but I haven’t unpacked that yet. Kelley exploits the cliched, dark heart of adolescence with ‘Satanic’ vocals and a literal pissing contest. A stream of urine puddles in darkness, becoming a magic mirror to a chthonic underworld. Kelley is literally taking the piss, making something new and taking us with him. At the end, a spectral troll appears hamming it up like a low-res Butoh dancer played by Kelley himself, naked, liminal and entrancing.

Revisiting Kelley’s work was also a legend trip. I have no idea if I would get him now—all-at-once—like this had I not had this decades long relationship with his work. Kelley is my own personal psychopomp leading the way-but through what? Surely away from midlife to something else more sublime.

Simon Wu’s review of the Tate show in Momus is so good: https://momus.ca/a-very-real-american-place-the-suburban-unconscious-in-mike-kelley/

Below is my blog piece from 2012

R.I.P. Mike Kelley

February 2, 2012

The news of L.A. artist Mike Kelley’s suicide has left me reeling and bereft. The world is suddenly a much less interesting place without him.

Mike Kelley was perhaps my first real art world love. I’d shaken off my infatuation with the Preraphaelites in high school and signed up for the whole art school experience as a rebellion, as a middle finger to all the other choices I didn’t have at the time. I had no voice of my own, no medium I’d mastered. I was stumbling along, and I stumbled on Kelley.

I remember going to the Newport Harbour Art Museum [Now the Orange County Art Museum] in 1988. This guy I’d never heard of had a solo show with video of performance art like The Banana Man and Kappa (a scatological Japanese fairy). There were things made out of crocheted animals. Freud and everything else was turned on its head. My heart beat faster, looking at this show. I went back over and over. Having never been to a circus, I felt like a kid who’d been taken to see the clowns for the first time: terrified and giddy.

Later, Kelley actually came to my school to speak. He was one of the few artists and writers who meeting in person was not a let-down. The school I attended in the late 80s did indeed suck– not least because the chair at the time was sexually assaulting and ritually humiliating women students. (Later, a group of women won a lawsuit against the school and my witness statement was integral to the case, but that is a matter for another post.)

In this darkness, Kelley was a light–he was a feminist artist, deconstructing received notions of the body and framing women’s work in subversive ways. He showed up to my Art Fundamentals class looking like a sinister mod, with his black bob and pegged trousers. He was funny, captivating, and able to talk about very dark things with a lightness. Beneath it all was a sly compassion. [When I spoke to him, he treated me as an equal—in a world of bully art men this was as disarming as seeing his work for the first time. In hindsight, he was also the first person to take me seriously as an artist.]

Though I ended up working in very traditional mediums–oils and etching on zinc plates–I carried Kelley’s work around with me as a reminder of what is possible.

I can only think his suicide is some sort of medical failure– depression too often goes untreated. I end with this youtube video and hope it isn’t in bad taste– in it Mike Kelley talks about what he’s buying at Ameoba Music in Hollywood. It sums up for me his unassuming presence and his creepy fascinations and characteristically gleeful attitude toward the abject. I can’t believe he’s gone.