NAPPING ON THE FAINTING COUCH OF GIANTS

or, our very own rest cure

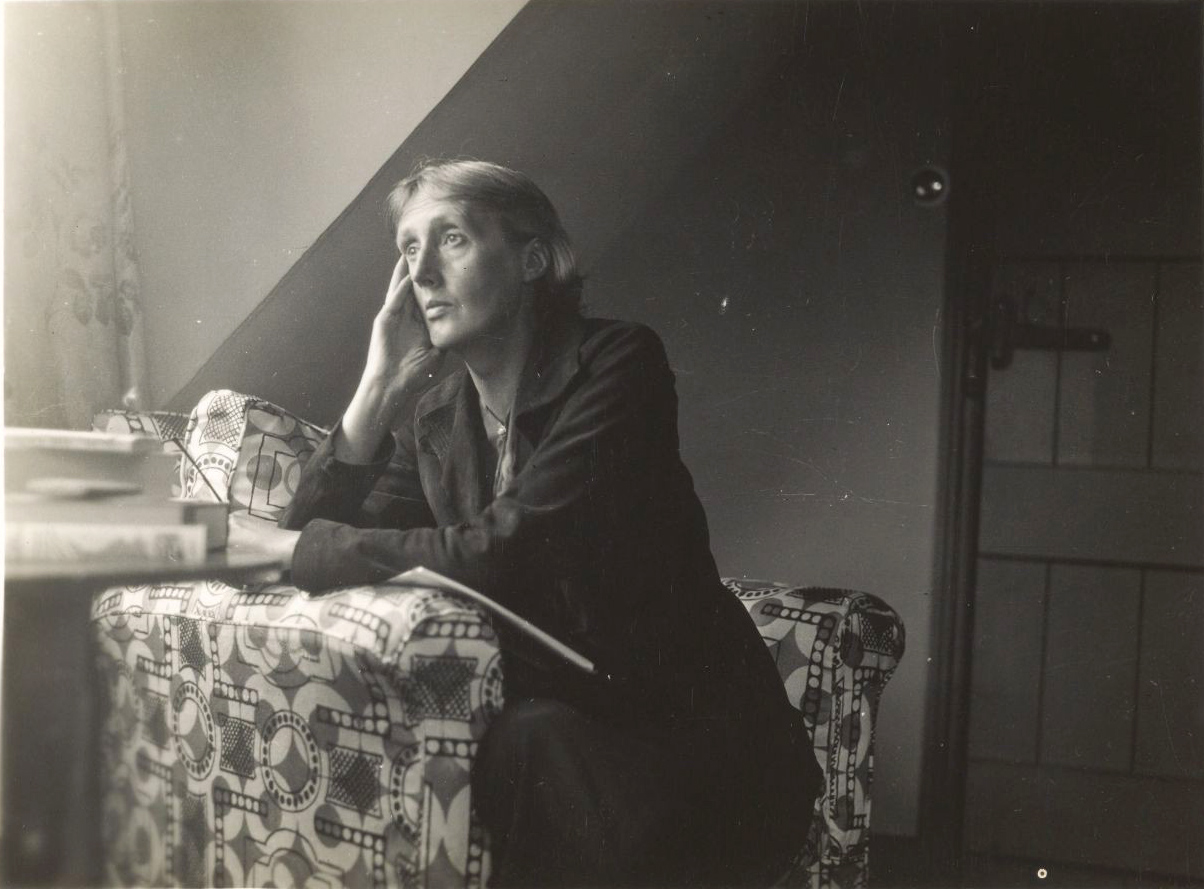

Illness is the great confessional

—Virginia Woolf, On Being Ill.

The invisibly ill are a brave yet shambolic company. We hurt. Sometimes we are full of immobilising sorrows or numbness. Our souls are so damn tired they have sacked out for the foreseeable. Misdiagnosed, given weird cures for centuries, we number in the millions, and most of us are women.

We are a vulnerable demographic. Unethical New Age healers and pedlars of bad advice and worse practices prey on us because traditional medicine doesn’t know what is wrong with us and doesn’t want to find out. Currently, there is little funding into autoimmune diseases and syndromes, and even less understanding and compassion in both in western and alternative branches of medicine. We are left with a lot of damaging, half baked solutions served up as wellness. We try these long-shots because we want to get better. Some treatments, like pacing—a kind of rest cure—have troubling roots in the misogyny of earlier practitioners.

Missives from the Verge with Allyson Shaw is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To find the right treatment one must have a diagnosis. Doctors are usually wary the moment we get out our notes, scripts and cheat sheets we bring to these fraught meetings. They are red flags. The practitioner can’t take on what we are saying, even though we’re being concise. They are thinking ‘my god I have to type all this out.’ Sometimes they actually are typing. Or they will scroll through arcane records while we talk, making faces.

Multiple chronic illnesses go on for years, lifetimes. If we are lucky to live to middle age it means half a century of doctors, diagnoses and disregard. Some heath care professionals are truly heroic, and others helpful, but many make it worse, and some, must be said, almost kill us.

There are ‘pain classes’ available on the NHS where the instructors insist that the only way to get better is to give up hope of getting better. They explain that once we stop striving to be better we will be. Is there evidence this thought based approach is effective? Ours is not to question.

No one really knows what ‘pacing’ means—not the physio prescribing it or the NHS pain classes meant to teach it. There’s prescriptive advice like only do activities for fifteen minutes before resting for an hour. We might ask why, but remember, this is our treatment we are jeopardising. Ours is not to question.

We might be writers and artists worried about our process. How can we kick out the muse every 15 minutes? What if we never get back in the flow? Will there be no grace left in the work? These are the most pressing dilemmas at the core of our being, our identities, yet ours is not to question.

Fellow spoonies—people with chronic illness—offer good advice about pacing: customise what we can do based on what the activity is and what our lives are like at that moment. This is a dynamic process, ever in flux.

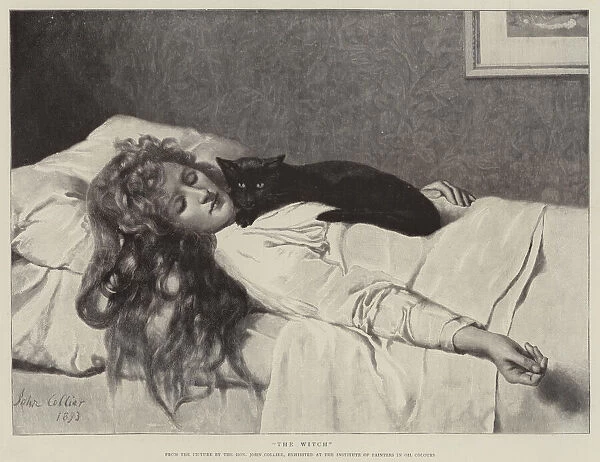

And yet, when we think we have worked out our days, forged a makeshift mastery over our yet-to-be-diagnosed ‘condition’ something changes. The pain increases to hitherto unknown levels and by the logic of pacing it means we have done too much, exceeded the 15 minutes of fame or labour or what have you, and have brought on a flare. We find new ways of being in those harrowing hours alone in a Poäng rocking chair, in our bed-office, haunted by beloved writers who endured the rest cure.

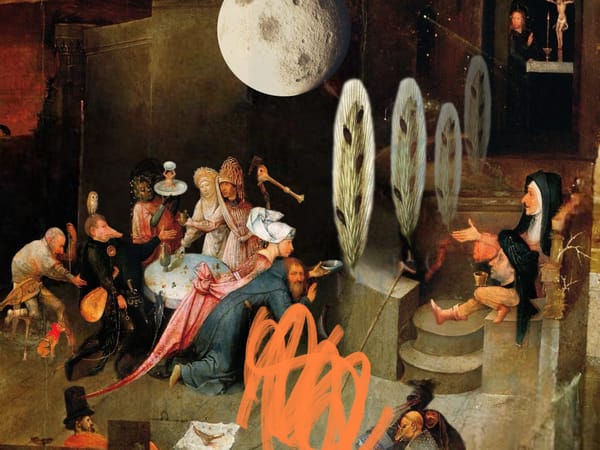

The rest cure was a treatment employed by the fashionable doctor Silas Weir Mitchell in the late 19th century. Originally tested on American Civil War Veterans, Mitchell adapted the treatment for women with the problematic diagnosis of hysteria. It involved isolation, immobility and massage. Charlotte Perkins Gillman and Edith Wharton were both Mitchell’s patients. Gillman’s horror masterpiece “The Yellow Wallpaper” is based on her recollections of the treatment. A patient was not allowed to read, write or see friends or family. The diet was several pints of milk a day and raw beef, pureed and watered down with medication, among other things. Patients who refused this food were force fed.

In 1915 Virginia Woolf survived a rest cure. She never received an adequate diagnosis nor treatment for what ailed her. In On Being Ill, Woolf’s changeling of an essay written while bed-bound, she mentions a visit to the dentist. At the time the essay was written, tooth pulling was recommended for fevers and “neurasthenia”—a vague diagnosis of the nerves. It is possible she endured this treatment, as well as the side effects of chloral.

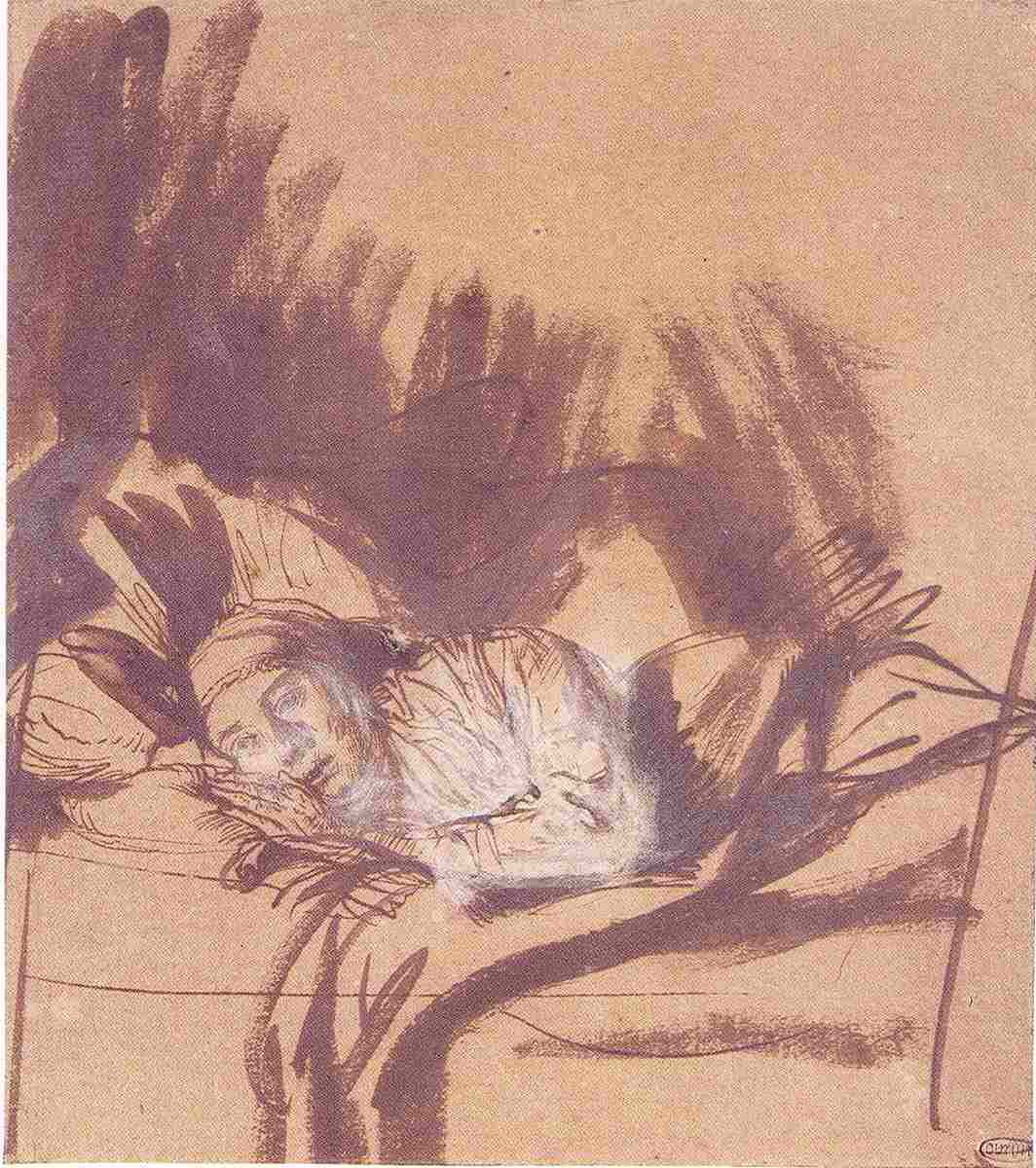

We—rocking chaired or bed-bound visionaries—have come to an understanding: this is a healthy reaction to a sick world, and the expanse of pain is a lens, a state that Virginia Woolf said was “partly mystical.”

Illness was Woolf’s “undiscovered country.” Here we plant our flag. Perhaps it is red. The land is peopled with unco* things, substantial creatures of reverie, story tellers from which we take dictation. For how long or how much doesn’t matter. Woolf also said, “But with the hook of life still in us, we must wriggle.”

*Scots for unknown, strange.

Missives from the Verge with Allyson Shaw is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.