ORCADIAN GOTHIC

—Frankenstein in Orkney—

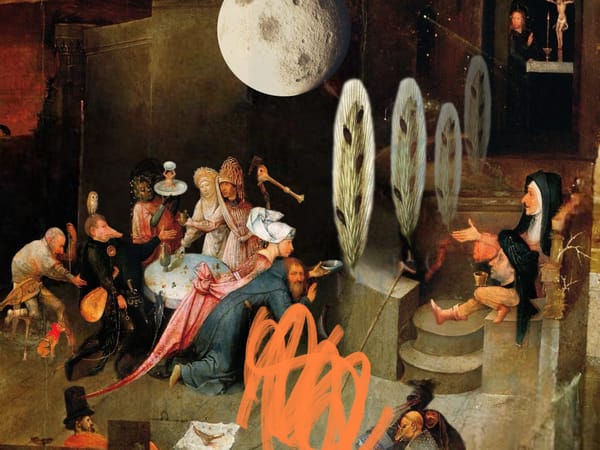

'I sat one evening in my laboratory; the sun had set, and the moon was just rising from the sea...'

Certain books follow us through our lives, reminding us of our past selves: an amalgam of lived experience, learned texts and memories retained in body and mind. In the last thirty years, I have re-read Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and the book has re-read me. In the parlance of our time—it me. Or they me—the doctor, the unmade woman, the monster.

In Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking 1818 novel, Victor Frankenstein flees through Scotland, over the Highlands to the ends of the earth in order to escape his stalker--the man he has created. He sits holed up in a croft in one of Orkney's 70 islands and sets to work making a woman.

Mary Shelley certainly travelled around Scotland quite extensively, but it’s doubtful she ever got to Orkney. The small island that shelters Frankenstein as he attempts to make a bride for his original creature is a vague place—a rough sketch of a rock with high sides ‘continually beaten by the sea.’ Frankenstein sees the island as ‘an insuperable barrier between me and my fellow-creatures…I desired that I might pass my life on that barren rock.’ Five ‘gaunt and scraggy’ islanders inhabit the place in squalid isolation--without even any fresh water if the account is to be believed. Victor Frankenstein rents one of three derelict huts—the thatch fallen in and the door off its hinges. The Orcadians he encounters are ‘rude’; according to Frankenstein, their penury has caused them to be ‘blunt’, ungracious and so benumbed by poverty that his nefarious work goes unnoticed. They still mend the roof and door at his bidding, though they don't notice he's got a body in there.

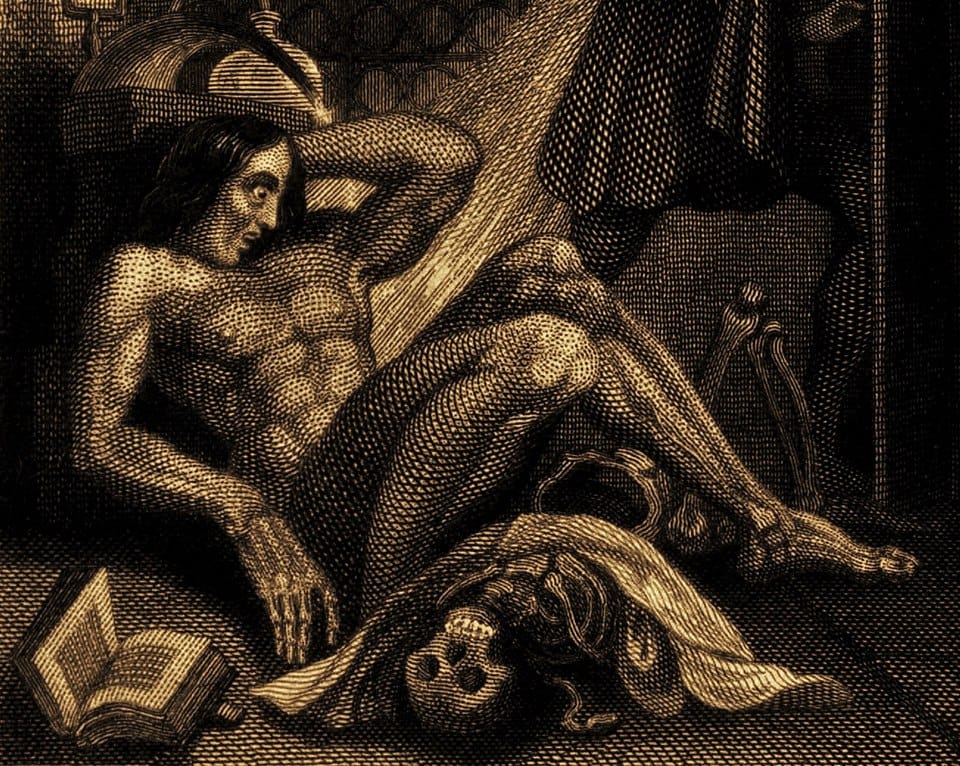

Victor Frankenstein knows this is a deal gone bad. He had promised his monster a being to do the emotional labour no one else seems willing to undertake--dispel his lonliness and make him feel real. Frankenstein wonders if the woman he is attempting to make will be rebellious. ‘She, who in all probability was to become a thinking and reasoning animal, might refuse to comply with a compact made before her creation.’ The contract is both the agreement with the monster, but also in a larger sense, patriarchal norms to which women are expected to comply.

She never gets made.

We don’t know which island he is on, and likewise, we don’t know who this new creature is made of, from whom the parts have come. It is likely she is a Londoner. Before departing the city, Frankenstein packs his chemical instruments and the ‘materials’ he has collected. As Frankenstein works in his ‘obscure nook’ in Orkney, his monster catches up with him. He peeks through the window at Frankenstein as he decides to abandon this new Eve—the ‘half-finished creature, whom I had destroyed, lay scattered on the floor, and I almost felt as if I had mangled the living flesh of a human being.’

Frankenstein ends up chucking her in a basket, rowing out under the cover of darkness and fog, and dumping her in the sea. The difficult cross currents around the islands carry him, and the plot, further and farther along.

Shelley’s masterwork is an epistolary novel told in bursts, one contained within the other like Russian dolls. First, a narrator is Shelley telling us the novel we are about to read is the answer to a late-night fireside dare. When all others at that gathering had forgotten about it and were instead enjoying themselves in the sun, she wrote. She tells us “The following tale is the only one which has been completed.”

Frankenstein’s amanuensis, Walton, is a failed poet. Walton declares, ‘for nothing contributes so much to tranquillize the mind as a steady purpose,—a point on which the soul may fix its intellectual eye.” Walton attempts to escape his failure by sailing aboard whaling ships headed for the Arctic. The rigours and trials of life on board fortify him with a sense of purpose. He writes to his sister from St. Petersburg with a Northerly sort of hunger: ‘What may not be expected in a country of eternal light? I may there discover the wondrous power which attracts the needle.’

Victor is traveling up from London. You know what's magnetic North --what 'attracts the needle' from London? Orkney.

Both Victor Frankenstein’s and Walton’s ambitions are thwarted by forces of nature. Walton's ship is frozen in Arctic ice for seven weeks. He's looking for a story to tell, and in rescuing Victor Frankenstein, half starved among the glaciers, he finds it.

When Mary Shelley arrived in Dundee, she heard stories of a ship called the Rodney, lost in the ice in 1810. Whaling ships returned to Dundee full of reeking blubber and stories of desolate arctic landscapes, deprivation, madness, and mutinies. Local legend claims Shelley began writing Frankenstein in Dundee. This makes perfect sense, even if the timelines don't.

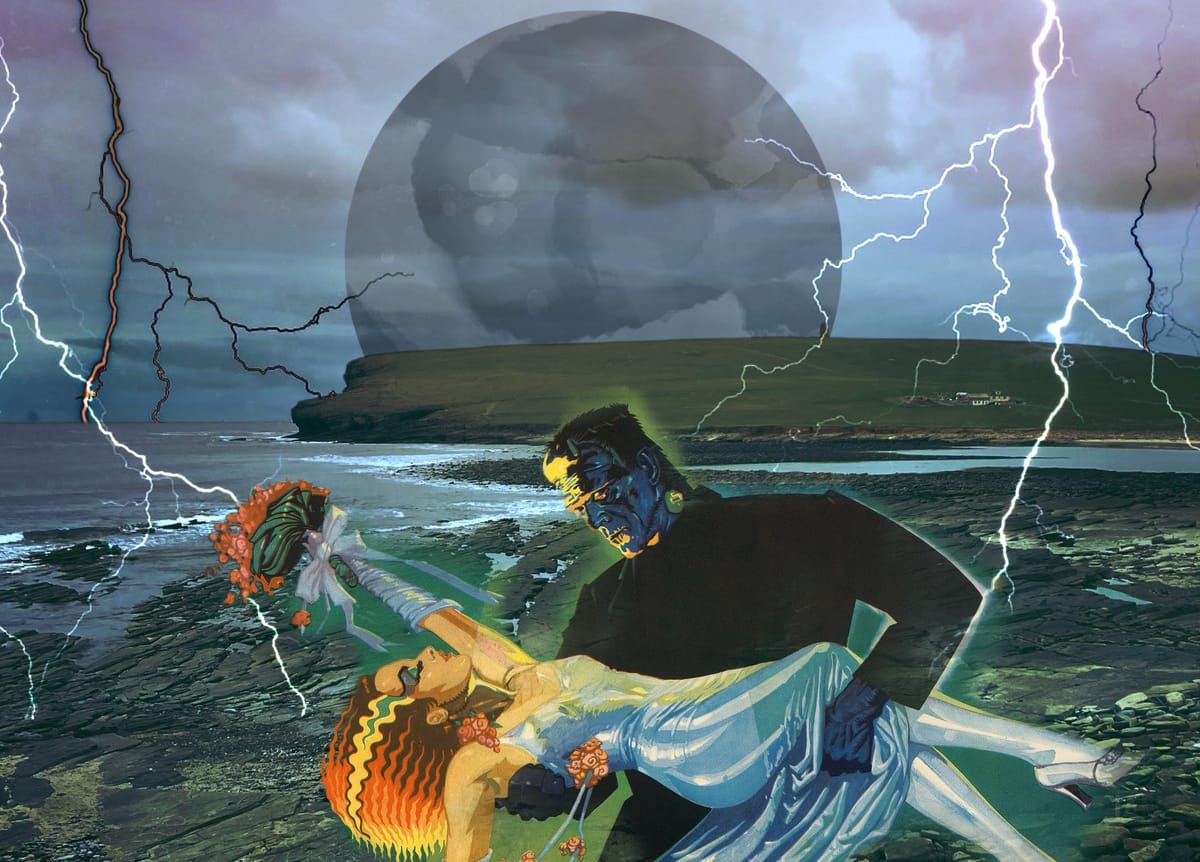

But wild, extreme Orkney–most likely unknown to Shelley--is the backdrop to the climax of the novel. The maker and the original monster confront each other, and the monster declares, ‘Beware; for I am fearless, and therefore powerful.’

‘Frankenstein’ has become synonymous with the creature. The two are one in pop culture parlance.

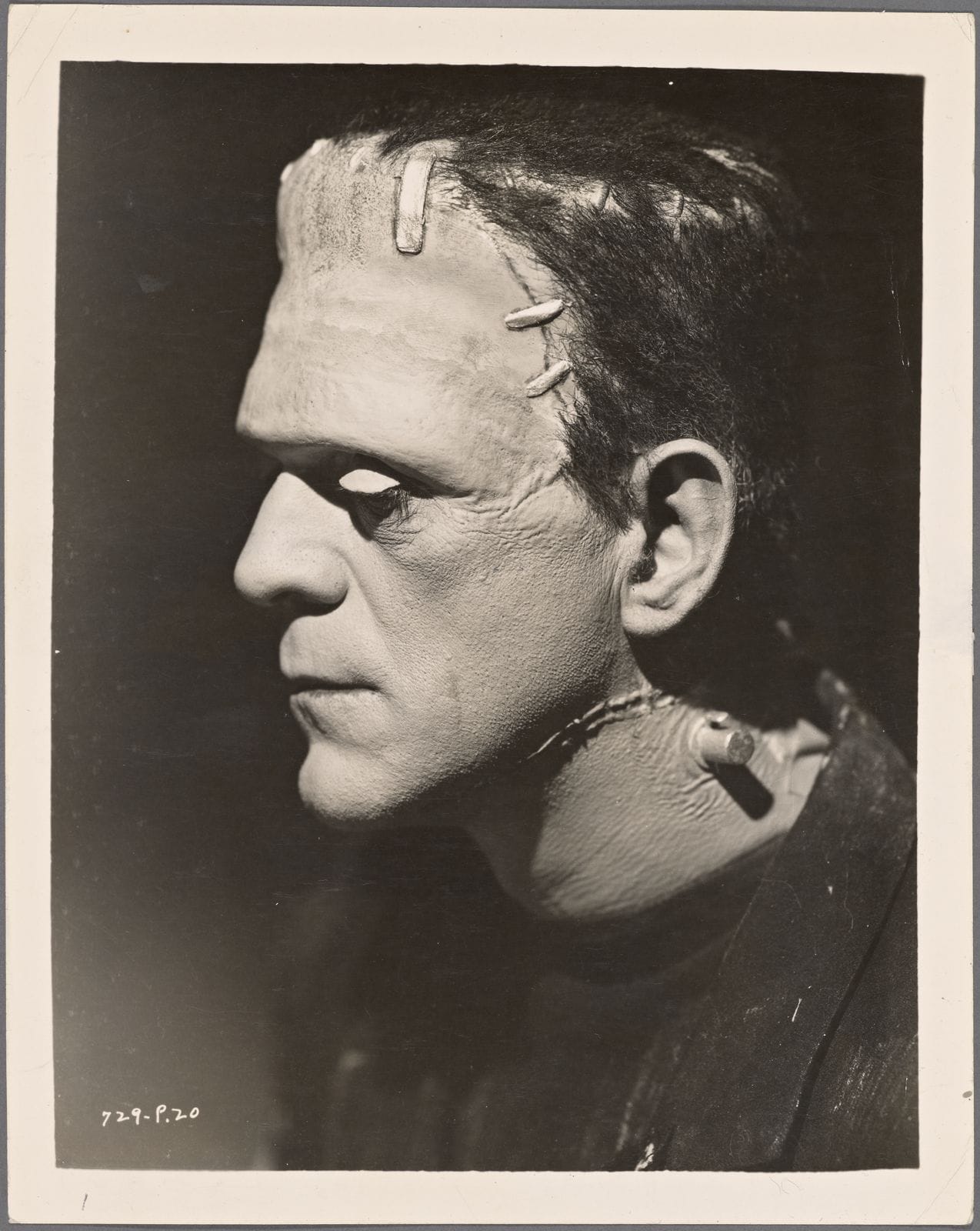

Shelley’s creature is described as ‘beautiful’. In this elegant image of Boris Karloff the literary monster and the Hollywood interpretation overlap.

Edison Production’s silent film from 1910 is the first film adaptation of the novel. Charles Stanton Ogle’s difficult monster is a shambolic ogre. You can watch the entire 12 minute film streaming on the Library of Congress website here. At 2:30 minutes in, Victor Frankenstein summons the monster like a witch at a cauldron. The creature emerging from a cauldron of caustic flames remains one of the most haunting scenes in horror cinema.

Of all the fictional Frankenstein’s monsters—it is Penny Dreadful’s Creature that comes closest to Shelley’s vision of the ravaged undead with a flowing, black mane of hair, black lips and a poetic, philosophical melancholy. In the series, the creature names himself John Clare and Caliban. (This scene played so beautifully by Eva Green and Rory Kinnear still gives me all the feels.) As fans say on Youtube, it’s 2025 and I still can’t get over Penny Dreadful.

It's a pity none of these adaptations touch on Orkney. Something I think about, anway.

Which Frankenstein’s monster is your favourite? What versions intrigue you most? Please comment!