SELKIE

a wee threne o strodie-wrack*

I am at St. Combs, a fishing village and beach named after the Pictish saint Columba. I was inspired by Sally Huband’s extraordinary book about beach combing, Sea Bean. I revisited this old pastime, something I did a lot when I first moved to Northeast Scotland. I scan the sand and shallow pools amongst the concrete barriers at the low shore. I intend to glean something, a talisman of some kind, but instead I am given a story.

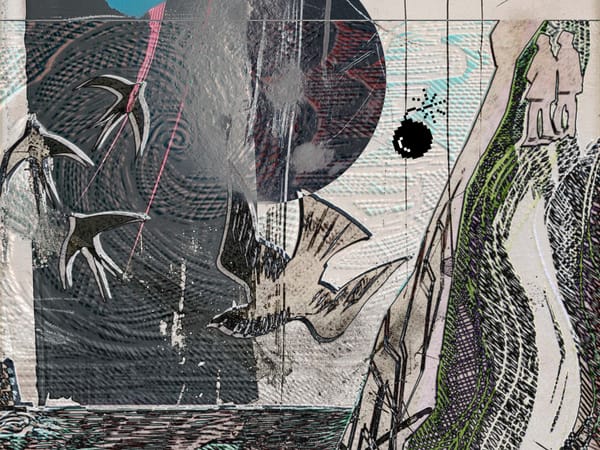

The massive cubes of the ruined seawall, a remnant from a world war, slide into the sea like the building blocks of a giant infant. Bladderwrack hangs in long tassels between crevices, and Laminaria or ‘tangles’ —feamainn in Scottish Gaelic— gather in pulverised hummocks spanning the length of the shore. Some bronze, others blanched white, are mixed in with the plastic detritus of fishing waste. I stand beside the tide pools where patterns of sunlight play out in the corners. The hyperreal green of gutweed and arterial red sea lace mix in with abandoned shells. A tiny, golden crab scurries for shelter.

I’ve stuffed my pockets with plastic, having forgotten a bag. The carelessness of people mixes in; abandoned things tossed about, rolling here and there—never at home. Their forms are broken down—a sea change rich and strange. A car battery becomes a deposit box of sand, ubiquitous plastic bottles and ropes shred themselves against the rocks where a shard of ceramic tiling—1950s bubblegum pink and covered in barnacles—sinks beside a fine wool cardigan, the kind I might wear. The sea has dyed it dun, but it was once surely black. The tide feeds on it like a moth. I try to pick it up but the sand holds on to the other half, as if something or someone beneath also tugs. Higher up, I find a shred of denim, the torn up leg of a long-john, and half a vintage track suit jacket in blue and red with a yellow zipper. There’s a mound, the size of a thigh, clothed in white sequins. It’s a synthetic mermaid skin—the scales of a gown glittering in folds and furrows. I reach down to touch it, dizzy with horror. Might this be a drowned person, buried in the sand? The dress is a fragment, only. To my relief, it clothes a stone. Are these garments from a lost suitcase, shipwreck flotsam? More likely they are the abandoned costumes of a blackening—a prenuptial ritual performed in the north of Scotland: a bride and groom dress up in old clothing. They go down to a beach where their friends and family pelt them with rotten trash before they have a wash in the sea.**

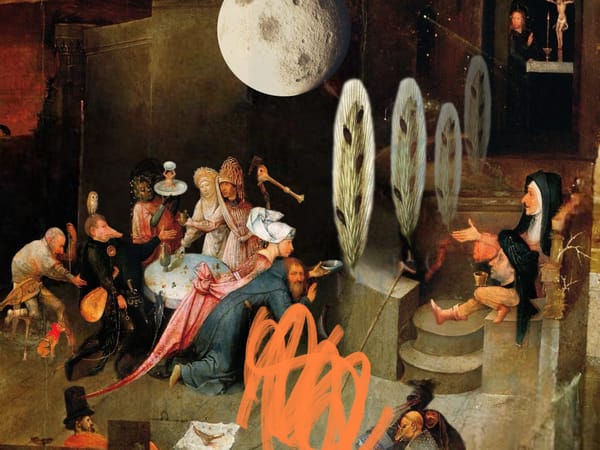

The old selkie stories tell of seals that leave their skin on shore to dance in human form under the moonlight. One day she—the captured selkie is always female—returns to her wild home with the help of her human child. The child is the one that finds her stolen skin and helps her get away. The old tellings emphasise the selfishness of the mother who abandons her child, but it’s the child who most wants her to be free. The child, the liminal halfling who understands both ways of being at once, will be the one to make things right again.

The selkie-woman dons the long johns, the jeans, and the gown. The cardigan is mis-buttoned over them, and the ugly tracksuit jacket tops it all, worn like someone who never cared about human things. She returns to her home shore, the grim place of concrete barriers built for a war she doesn’t remember. She peels off the clothes and leaves them on the rocks. Naked and alone, she unfurls the dry old pelt in the salt spray. It binds her as the tide drags in, and her with it.

- Scots meaning “a small song of flotsam-gown”

** (This custom was the inspiration for my folk horror story, The Middening, published in Fireside. You can read it online here. https://firesidefiction.com/the-middening )