The Wonder Cabinet of Culver City

--revisiting a Los Angeles enigma via a 24 year old webzine.--

In 2001, I was waxing lyrical about a mysterious shopfront museum in Los Angeles located at 9341 Venice Boulevard. Founded by film set designers David and Diana Wilson in 1988, The Museum of Jurassic Technology is an trickster-ode to the institution of the public museum. Writing this essay first connected me to my lifelong friend, Lori Matsumoto, who was one of the caretakers of the museum. It was through Lori that I was invited to many a marvellous fête after hours at the museum.

I had been visiting the museum for several years before I wrote about the fascination it evoked. The museum is a meditation on the very act of musing, marvelling and wondering. It strikes me that this particular emotion—wonder—is in very short supply these days of dour dichotomies. At a time when we have diminishing capacity to hold space for paradox and contradiction, I wanted to celebrate this space that revels in ambiguity.

The museum is still open today, eliciting hostility from an online audience incapable of tolerating ambiguity. The blog post “Internet Randoms Fact Check ‘Jurassic Technology.’” from the Los Angeles County Museum on Fire rounds up a few gems to which an astute annoymous commenter replied:

“I think it is a tribute to David Wilson's art that people are still being intellectually ambushed by this Baroque masterpiece of the post-modern era. The Getty knows it, the Macarthur Foundation gets it [Wilson received a genius grant for his work.] and so do the many dedicated art lovers who make their ways to the museum from all over the world. I suppose it's unfortunate that MJT alienated some of these visitors, but then isn't the natural audience a small and secret society of Illuminati? Say the word and the door opens upon treasures the eyes won't believe…"

The essay reprinted below was initially published in an online zine M and I edited called Die Cast Garden. At the last full moon I published another essay on the pre-gentrification marvels of downtown LA from the same zine. You can read it HERE.

I coded Die Cast Garden using Dreamweaver made illustrations with Fireworks (before Adobe bought this software the pair were glorious, but I digress.) I found the zine on the miraculous Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. 20 some years ago, Die Cast Garden was my answer to publishing in general—I couldn’t find an agent or publisher for my work so I made zines—xeroxed paper ones and HTML websites. Long may that spirit continue!

Not far from Sony Studios, there's a little spot of genius at 9341 Venice Boulevard. Perhaps some of you have seen it– maybe even been thereThe museum of Jurassic Technology. It's a small, unobtrusive storefront without windows. At the door there's a tiny empty case and fountain, which remain a mystery.

On my first visit to the museum many years ago, Mr. Wilson, the proprietor and artist behind the museum, was outside playing the accordion. He wore horn-rimmed glasses and a wool sweater in the L.A. sun. He greeted my friend and me as if he knew we'd be coming all along, and welcomed us into his dim little wonder cabinet of a museum.

An interesting biographical note, Mr. Wilson worked in The Industry, [meaning the film industry] and at one time lived in a small house out someplace rural, with no electricity. He and his wife used their earnings to fund the museum. This is the kind of brave single-mindedness that inspires me, and I have been back to the museum over and over for the past seven years, tracking each new exhibit, each elaboration on the many themes Mr. Wilson explores.

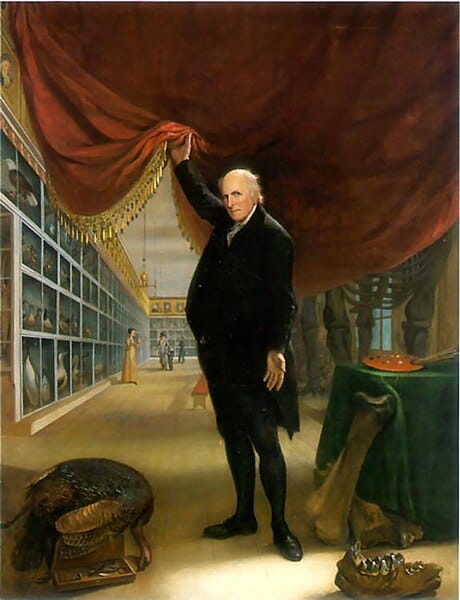

One of the first themes I noticed at running through the museum was that of the arc, the biblical arc; Noah's archiving two by two, a metaphor for the curatorial project. There's a small scale model of the arc in gallery one, a compartmentalised box looking very unseaworthy, and this theme is continued in another room, in "The Garden of Eden on Wheels," devoted entirely to trailers and their mobile collections of pincushions, bottles and other domestic objects collected by people who live in trailers. Having lived in an old trailer myself for many years, where your habitation is miniaturised and portable, I understand this project completely.

It's fitting then that the next room would take the idea of the miniature to the realm of absurdity– in the exhibit titled "The Eye of the Needle, the Unique World of the Micro Miniatures of Hagop Sandaljian," where the Pope and characters from Disney, like Mickey Mouse, Snow White and the dwarves (of course) have been sculpted on heads of pins, painted between heartbeats.

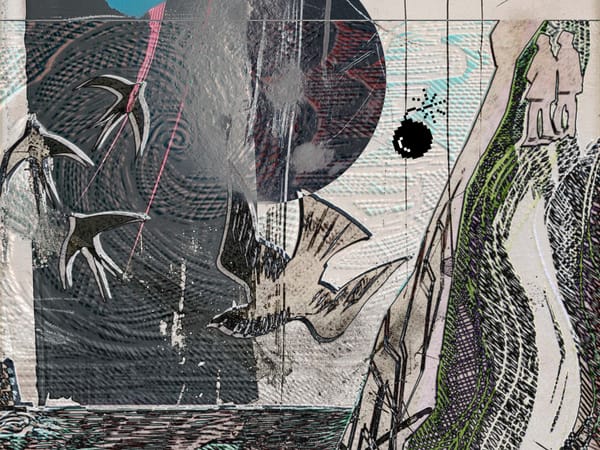

Back in Gallery 1, the theme of the cone or horn persists. This shape continues through all the exhibits of this gallery. The deprong mori, or little bat, a.k.a myotis lucifugus or "piercing devil," emits a cone shaped sound that enables it to travel through thatched lean-tos and metal. There's also the horn of a Mary Davis Saughall mounted on the wall, looking very much like a calcified dread lock. In the Sonnabend-Delani rooms, Sonnabend's "cone of memory" is a convincing but possibly bunk explanation of remembrance and forgetting. An etching of a conical Tower of Babel decorates one wall.

The Tower of Babel itself is a theme-- there's the Misch/Webster Gallery, featuring "No One May Every Have the Same Knowledge Again: Letters to the Mt. Wilson Observatory, 1915-1935." These letters, scrawled on Christmas postcards or carefully typed, are moving and comical in their certainty. One letter by "Edward" insists, " I have found the Key to all Existance.[sic]" and "the Moon Is practically all Water…" I've guessed at the authenticity of the letters-- they all seem so perfectly absurd and poetic. One can see where David Wilson's sympathies lie: with the quacks and fervent guessers, these paranoid wonderers.

The new exhibit, "The World is Bound With Secret Knots" is devoted to one such wonderer, Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century monk who studied magnetism and conjectured on the shape and order of the universe. The exhibit features beautiful dioramas of his ideas, and a bell wheel. A Tower of Babel appears here again in a horned shape, Kircher's vision spindling to the heavens. This exhibit is the most seductive yet. As you enter, you first hear the ethereal, insistent sound of the bell wheel, but the ringing remains a mystery until you are in the main room where the bell rings and wanes over and over as you view the dioramas and "magnetized" wax figures suspended in glass globes of water.

What becomes clear while looking at the Kircher exhibit is that the dioramas do not exist to teach history or concepts, as in other museums, but to concretise the poetry of mistakes, the convincing fictions. That is what I love about this place--it has shunned objective truth and "factual" history and instead made these principles subject to narrative. These "lies" are often more profound and precise metaphors than the ones we are given with scientific "realities" today. It's not the archaic ideas themselves that do this, it is David Wilson's way of presenting them that makes them so fascinating.

I love to go to the museum with friends and conjecture about which exhibits are based in fact and which are fabrications of David Wilson. There's a wonderful Book called Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder, by Lawrence Weschler, which you can consult if the ambiguity of the place is really bothering you (or if you live too far away to visit). Weschler did quite a bit of research and concludes that some of the most improbable displays in the museum are in fact true– like the ant which scales a high tree and impales itself after inhaling a spore. But I insist that deciphering the fact from fiction is not necessary to get this place, and in fact, a preoccupation regarding the exhibit's factual validity fully misses the point. One must look at the museum as an examination of wonder itself.

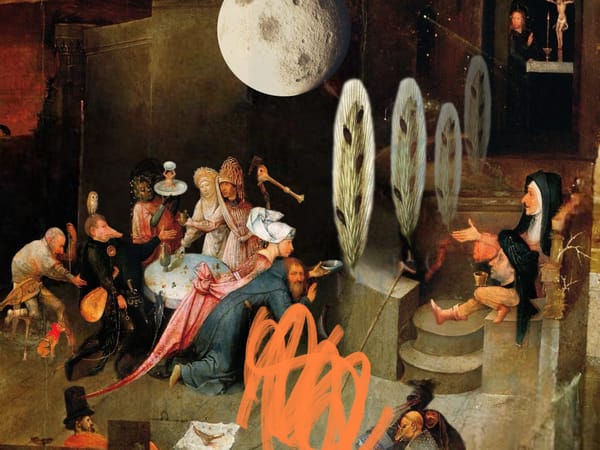

It recalls the fantastical and often misguided project of the 17th century wonder cabinets– collections of curiosities and oddities collected through travels and trade, belonging to noblemen who supplied curator's narratives that are often humorous and poetic. The photographer Rosamund Purcell has often explored these collections in her photographs, and indeed, the museum has a room devoted to her work featured in her book, Special Cases.

In the same vein as these 17th century collectors, the Thum Room's "Tell the Bees…Belief Knowledge and Hypersymbolic Cognition," documents superstitions. The room is very dark, the small cases spot lit, barely illuminated. One must lean in closely to have a look. It’s spooky and intimate. The accompanying plaques strain the eyes, but it's worth the effort. Here are the poetics of post-hoc reasoning: a mother's tears will keep a dead infant from heaven, after a death in the house you must tell the bees of the passing, a duck breath's a curative, a sprinkle of matriarch urine will bring luck on New Years Day.

After you emerge from the final exhibit, you can go to the small library, a civilized corner where you can browse a collection of books as diverse and strange as the exhibits themselves. You'll forget you're in Culver City. I always take time to look at the books on sea monsters and medieval orphans.

The museum is branching out and has recently acquired the entire building where it is housed. To find out more about the museum and its future plans, go to http://www.mjt.org.

[The museum’s website remains unchanged almost 25 years later--still in basic HTML with a tiled background--with the exception of a page about pre-booking your visit that includes a floorplan of the museum galleries.]