TRYOUTS FOR THE HUMAN RACE

--on silencing and generative AI--

An English teacher in one of my high schools would say ‘if you can’t spell a word, it’s not yours to use.’ She made us stand at the board and write out words like bourgeoisie. The atmosphere in that room was very Lord of the Flies. At least she got me to read Joyce—though she did dismiss him as being ‘too Catholic.’

You know who always spells a word correctly? A machine.

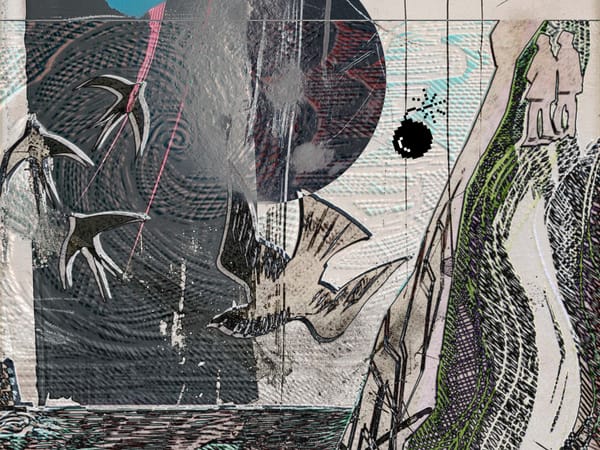

This has changed everything. Generative AI has taken on the messy work of writing and generating ideas so we are left--to do what? Scroll on our feed of choice? Play a video game? Shop? Never mind these models have been trained on the copyrighted work of others, churning them in a plagiarist slurry and spitting out something else we can say is 'ours'--a thing without context, citations or attribution.

Once, not that long ago, it meant something to be able to wrangle language, make it 'yours to use.' There was dignity, meaning, and connection in this hard-won skill.

When I taught writing to adults in night school, I bigged-up the whole ‘learning to write’ thing. I'd bring out statistics about literacy and pay grade. I promised them if they learned to think and write--for the two things are inseparable--it would increase their quality of life. Look at me! My life is better because I can think critically! I can write! Some of them drove past me in brand new cars as I waited for the bus home. My cover was blown.

Teaching night school was a long way from where I started, though, as a dyslexic struggling to spell. (I had found a way to walk in the footsteps of Virginia Woolf– not a dyslexic but certainly neurodiverse--who taught night school to adults at Morley College.) Here I was, voicing things I wanted to believe, even as I doubted their veracity. Now I know them to be untrue: writing will not improve your quality of life, gain you respect, or earn you money--but it might just be how you survive. No machine can do that for you.

When I was a college sophomore at San Francisco State University, there was this Composition teacher, a slight woman with fluffy, taupe-coloured hair styled in what was probably a bob when her inept hairdresser cut it, but in the San Francisco fog it dispersed to a glum diadem. She wore her weariness like a mantle thrown over her blue cardigan. But what I remember most is a single lesson, unsheathed from her discontent like a blade: a free-writing technique. If you are blocked, just start moving your hand across the page. If something is in the way emotionally or intellectually, just write about that, give it its due.

She had obviously done this often.

I didn’t like that teacher very much–she was joyless and especially exasperated with me–but her method was golden. Most other teachers I'd had didn’t really care about my inability to spell, my slowness in reading. No one ever clocked me as dyslexic. Perhaps I had been spared. This SFSU teacher thought I was lazy. I was smart enough to do well, so why did I write so badly? (Truthfully, I'd spend painful hours looking for errors. I simply could not see what I'd gotten wrong, and it became increasingly difficult to ask for help the farther along I was in my education.)

This Composition teacher chose the Hemingway story, “Hills Like White Elephants” for us to write about. I thought how sad that she should choose this story, out of all the stories in the world, as a paragon of form and style. The narrative is simply a conversation between an American couple waiting for a train in Spain. They drink beers and talk around about an unwanted pregnancy. I still shudder when I read the diction the man uses when he proposes “a simple operation...It's really not anything. It's just to let the air in.” My essay addressed abortion taboo, and I probably worked in my activism doing clinic defence at the time. For starters, there were a lot of misspelled words. She told me I had to write it over in order to pass. I remember thinking that writing it over would do no good–I had already written it over many times. I understood the rules but couldn't 'see' them in the context of my work. There was this sinking nightmare feeling that would become increasingly familiar to me, even now, with many more tools at my disposal.

“I was trying. I said the mountains looked like white elephants. Wasn't that bright?"*

You'd think, with all that terror wrapped up with writing, I would be the first to embrace a machine that would just do it for me, right? That's the answer. Surely that's one reason why others use Gen AI now, to circumvent this dread of error, drilled into us by teachers who had this way of thinking about writing drilled into them.

The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white.

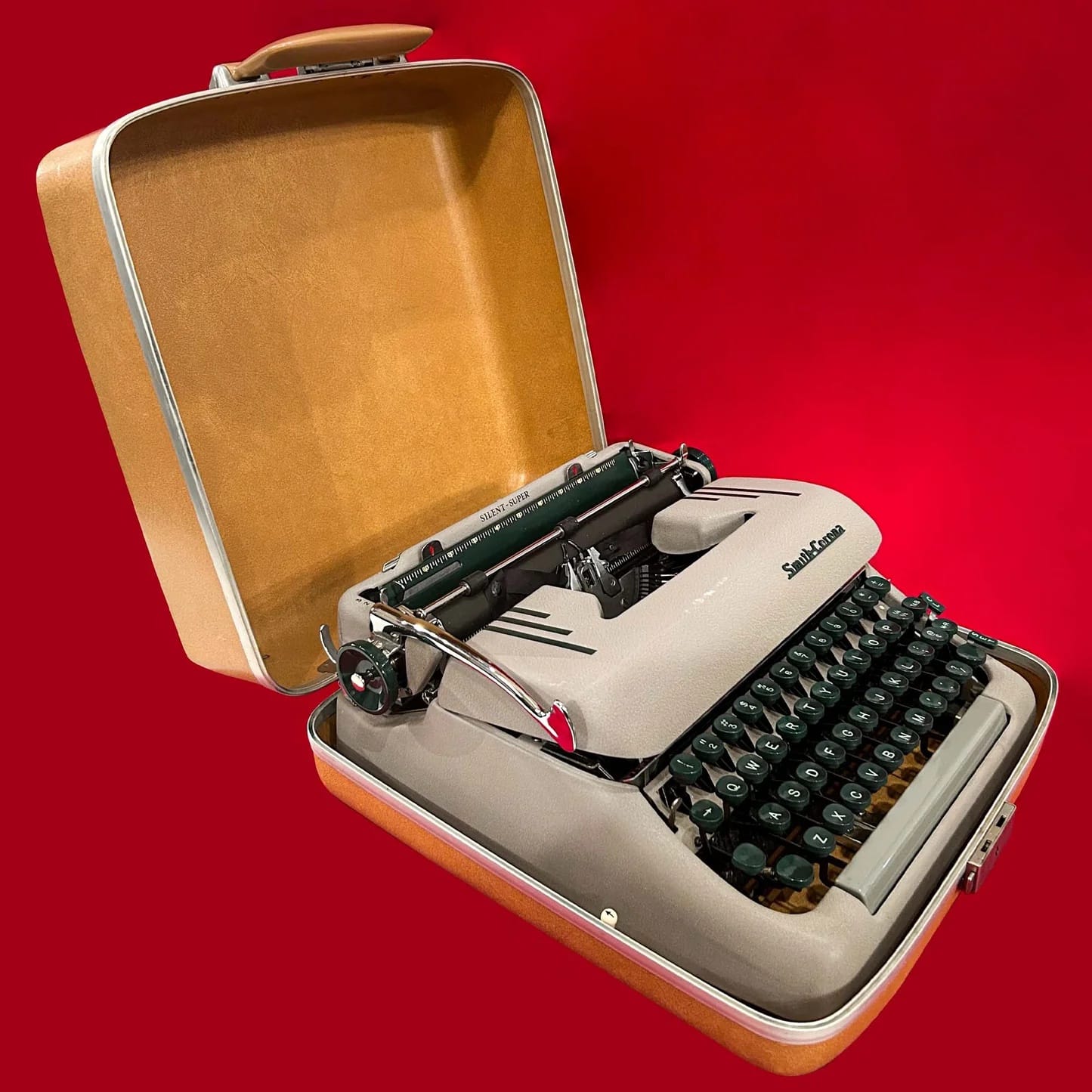

As an undergrad, I majored in Studio Art so I wouldn’t have to write too much. I wrote poems because there were fewer words to get wrong. Each word took such effort to get right; the devotion and economy of poetry suited me. I had a methodical Smith Corona typewriter that once belonged to my father. Theoretically portable, it had an integral, hard case with a sturdy handle. The apparatus weighed several pounds and I carried it with me to each friend’s couch, every tiny room and the trailer I inhabited. The tape wore out and I didn’t know how to get a new one. A boyfriend gave me an electric machine with a tiny screen—a word processor--to replace it. Someone else gave me a little electric dictionary, like a word calculator, to check my spelling, but I continued to write poems on that old Smith Corona. Eventually I must have changed the ribbon somehow because I kept up that a physical act of drumming each letter into the page even into the mid 90s. The swish & thud of the typewriter’s emphatic gesture was part of the process.

I learned to touch type on a computer keyboard with a program that played inane music for you to keep time. It felt like dancing. [As an aside, I am obsessed with this website that turns keystrokes into a song.] Autocorrect and spellcheck mean I can now pass as a neurotypical adult; I can write a book-length work that will see the light of day. If you wait long enough, machines evolve to help you. So is generative AI really that different from these other revolutionary tools?

"Everything tastes of licorice. Especially all the things you've waited so long for, like absinthe."

Jig, the American waiting for the train in Hemingway's story, is bored and full of self-doubt when she declares the taste of ennui to have this particular flavour. Generative AI machines devour our work and regurgitate it—until everything tastes 'like licorice.' In the long writing game I have played, this usurpation seems to have happened suddenly. After a life of learning to write so that I would be taken seriously, so that I could find meaning and think critically, it turns out it’s actually grist. In a world where content has replaced meaning, no one with power takes writers seriously.

I have left social media platforms where I once had an audience because I just couldn’t stomach it anymore—the idea that a machine was manipulating the messages of friends and other writers and artists in order to keep me scrolling. It clearly failed, and I deeply rebelled at this invasion. What I've posted on places like Facebook and Instagram is fodder for some behemoth that has already been fed the full-length works of my peers via the pirate website LibGen.

People who use AI to generate 'content' (never art) are perhaps trying to short-cut the guess work, heartache and years of soul-infused labour that goes into making work. Maybe they don't believe they have a right to language–to critical thought. Has this been drilled out of them? It may seem easy to use but the cost is high–both environmentally and aesthetically. Generative AI uses huge amounts of energy and clean water, and yet the results are impoverished, fool's gold.

There are no short-cuts to the transformative magic of learning to write. One learns this only with agency, as a reading-apprentice. By the logic of late capitalism–if learning to write is this much work with so littler return, is it even worth doing? AI will do a solidly mediocre job of it, so why even try? You'll never have to rewrite anything for anyone ever again. Shouldn't this be something to celebrate?

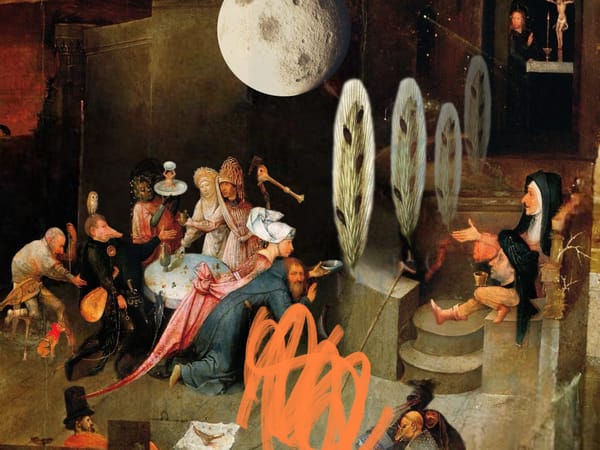

Writing is a uniquely human process: the alchemist-poet’s techniques enable us to transmute absurdity, tragedy and existential dread into golden meaning. Language itself becomes consolation. This process can't be cheated, yet in the tyranny of the marketplace, these hard-won skills are seemingly obsolete.

“…once they take it away, you never get it back.”

I wanted to wait until I had an answer or perhaps some good news to write this post. I waited for perspective that never came. Perhaps if I fed my dilemma to ChatGPT it would give shape to this thing that’s in the way of me writing.

It will undoubtedly taste of liquorice.

AI will eventually be exposed as a white elephant, a business venture with costs far outweighing its value, but how much of what we know to be true about ourselves will be lost in the process? How much is already gone?

Hey there, teacher whose name I can’t even remember now, I am giving this particular hell its due, writing it out to get to the other side. Thanks for passing that skill on to me. I survived you, and so many like you–simply by continuing to write.

That manual typewriter, now long gone, is looking pretty good right now.

“Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?”

*Quotations from Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants”, 1927.

Title is a reference to this Sparks song that's in theory about sperm, but could also be about Gen AI.