UNPACKING MY BOOKS

On Walter Benjamin, bibliophilia, and word hoards

After moving to Orkney, my books were the last thing I unpacked. They sat in a ramshackle pile in front of an empty bookcase, admonishing me.They gathered dust, their corners tufted with cat hair. I put it off because I knew it would be emotional. I would have to confront not only the near-impossible amount of research that went into the writing of Ashes and Stones, but also each tome that had somehow survived with me containing the essence of a particular month or year in my life, the same life that brought me here, to Orkney.

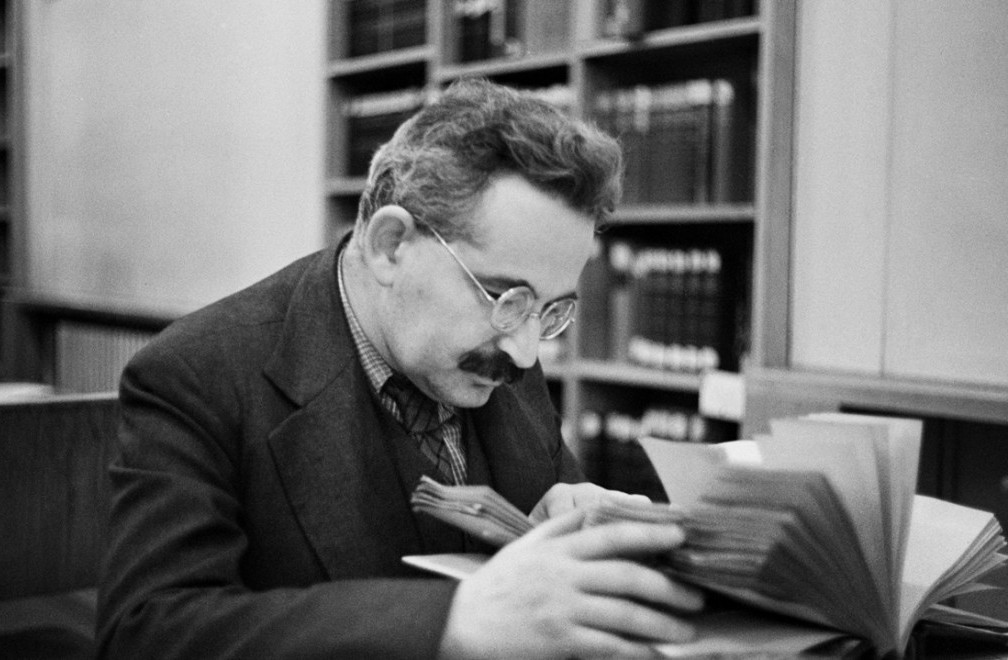

In hopes that it might give me a bit of courage, I revisited the intimate camaraderie of Walter Benjamin’s essay Unpacking My Library. Written 1931, after the philosopher and critic moved into a new home, it reads like a confession. I felt, as I have so often, that I am in a dialogue with him.

I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am. The books are not yet on the shelves, not yet touched by the mild boredom of order…

As I shelve my books, what becomes significant are the vacancies—books that should be there but aren’t, like Humphrey’s translation of Ovid, the spine cracked, pages shuffled, loose, Shakespeare’s The Tempest, extensively marked up in the margins, or the fairy tales of Oscar Wilde. My few shelves embody the pain of the exile, the immigrant. Adrift outside of academia, I parted with many texts I had used while lecturing at University and at junior colleges in the US, despite initially dragging them with me over an ocean. When I couldn’t find work teaching in the UK, I purged them all, as if they personally had betrayed me. Chronically unemployed and working as a dogsbody temp, they were a reminder of a passion that had no outlet.

…share with me a bit of the mood—it is certainly not an elegiac mood but, rather, one of anticipation which these books arouse in a genuine collector.

For Benjamin, a serious book collector, the object itself embodied emotion and memory, and in collecting rare books, he ordered this universe.

When I talk about my books, I am talking about myself—what has chosen me, accompanied across many state lines, national borders and vast bodies of water. There are books written by friends old and new, books I have read countless times and ones I have yet to read. There are books that have saved me and books that changed me. Books that are a surrogate family.

…what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order?

My word-hoard is small, selective: I have a row of TBR, and tomes I feel I must re-read. I have favourites that have become touchstones of hope: good writing will eventually find its way in the world. There’s a row of reference books and guidebooks to the natural and unnatural world, to this world and the other beyond the veil.

Each has its place: a dog-eared Emily Dickinson—her urgent dashes keep speaking even when the cover is closed—a sibilant spinster hymnal. There’s a lot of sea on the shelf—starting with the first book I ever owned—an elaborately illustrated 1960s copy of Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, a gift from a relative who brought it back from Copenhagen. A fleet of surrogate sea-faring novels leans beside: Moby Dick, China Mieville’s The Scar, Marquez’s Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor. Some books I re-read because they teach me about voice, like Margarite Duras’ The War and Lynda Barry’s Cruddy. Other books have saved my life, over and over. Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber acted as a deep deprogramming from patriarchal norms. I read Collette’s Vagabond in hospital after almost dying. Collette’s words were the breadcrumbs I followed back to the living. I had the foresight, while suffocating, to put this book in my bag before heading to A&E— proof that one can save one’s own life with the help of books.

…a dam against the spring tide of memories…surges toward any collector as he contemplates his possessions. Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector's passion borders on the chaos of memories.

When so much text is now ephemeral, algorithmic, subjected publicly to base metrics—the book presents a slowness, an intimate contract between writer and reader that can span hundreds if not thousands of years. It is a cliche to say that reading is a collaborative effort with a writer, but it’s true. The book as an object becomes a storehouse of time and memory. To be alone with a book, subsumed in its world for hours, weeks and months, is even more important in a world where our visual and verbal diets are determined by advertisers’ algorithms.

You have all heard of people whom the loss of their books has turned into invalids, or of those who in order to acquire them became criminals. These are the very areas in which any order is a balancing act of extreme precariousness.

A first edition of The Hobbit found at a Cancer Research charity shop in Dundee recently sold for £10,000. I was forced to read this book in school when I was ten, an undiagnosed dyslexic, one of the first ‘grown up’ books I read from cover to cover. It confounded me—I could not experience it as a linear narrative; I only retained imagistic snippets of giant spiders and Golum. The teacher who choose it for us was a dour matron decked out in polyester shirt dresses and frosted orange lipstick. She offered The Hobbit up as if it were a special treat. Only now, as a grown woman the same age she would have been in 1980, do I see her as a little girl delighting in the tale, living through a world war with this book as a consoling object. Perhaps she held the first edition in her chubby girl-hands. It has a pea green cover, the same colour as the first edition of Ashes and Stones. I like to think that maybe she is the one who bought the charity shop find, having made good investments with her teacher’s pension or won the lottery, but she is most likely dead by now.

Might we need a Voight-Kampff test for a poem? A love letter? A eulogy?

I have never bid on a book at auction as Benjamin had, not even on eBay. I don’t fetishise books as objects. Having known vinyl collectors, I realise collecting is really an impulse to build a citadel of discernment around oneself, to secret one’s identity away in a hoard of order. (I confess I lovingly collected and tended a shoebox full of ticking Swatch watches from the 1980s. Down on my luck, I had to sell them all. But this is a topic for another post.)

I didn’t even really understand editions and reprints until my own book sold out its first printing less than a month after publication. I had to figure out what all the little numbers in the front matter meant, and what a print run was. Such was my prelapsarian moment.

Books are magic, perhaps even more so in modern life with its erosion of privacy and the unasked-for firehose of overshares that is social media. Benjamin wrote his most famous essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in 1935 during the Nazi regime. I often wonder what he would have made of this age of AI artists and poets. Benjamin argued that a work of art has an aura of the time and place in which it was made, as well an energetic stamp of the person who made it. As a work is reproduced, the aura of authenticity decays.

Now, machines cannibalise human creation without attribution. AI works are elaborate plagiarisms becoming undecipherable from art and writing made by people. There might be tell-tale signs in a work produced by artificial intelligence—for instance, AI can’t draw hands—but AI work is increasingly refined, passing as human. Might we need a Voight-Kampff test for a poem? A love letter? A eulogy? Perhaps we are approaching a time when, like the replicant detecting machine in the film Bladerunner, machines will tell us what has been made by a human and what is created by a machine.

Etsy, what was previously a ‘handmade’ market place, has one of these interrogation machines in the form of an algorithmic bot. It is the place where, unfortunately, I make most of the money I earn to live. In the height of irony, the Etsy machine removed one of my handmade items for sale, claiming it was not handmade.

What does this have to do with books? I’ll tell you. A fast-moving tyranny is at large, and we must take shelter from it any way we can. I choose to take cover in the pages of a book.

Only in extinction is the collector comprehended.

Benjamin committed suicide at the age of 48 as he fled from the Nazis, nine years after writing Unpacking My Library. I often wonder what happened to his beloved library, who bid on his books, and what villains profited? What did he read in the few years he had left with his books? At the end of the essay he erects the dwelling of a bookworm and disappears inside.

Some days I think I should buy a bigger bookshelf, begin collecting anew. Each book would store memories I’ve yet to make. I put that project on hold and instead go to the library in town, my bookworm-house. My selections there rub shoulders with the lives of other readers, our date stamps marking our communal time spent with the books. On a good day amongst the stacks, I manage to vanish.